The competition has been postponed until further notice.

Deadline Extended to Noon, Friday 17th March

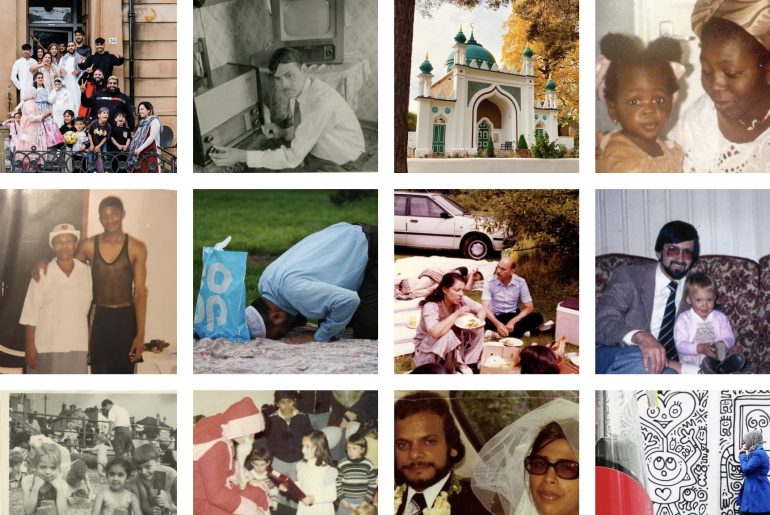

The Everyday Muslim digital photography archives are one of the UK’s largest public collections of images documenting everyday Muslim life in the UK.

Entrants to the competition will be invited to submit their photos to this unique public collection. They would also be selected to be part of exciting new Everyday Muslim projects that could see them featured in a publication, exhibition (National partner TBC) and documentary to mark our tenth anniversary in 2023.

The competition’s theme is ‘everyday Muslim life’, and any budding photographer from the United Kingdom and Ireland can participate. Submissions can be either new or old photos. Photos can show activism, art, buildings and places, celebrations and festivals, childhood, education, faith, family, food, travel, home, leisure or work.

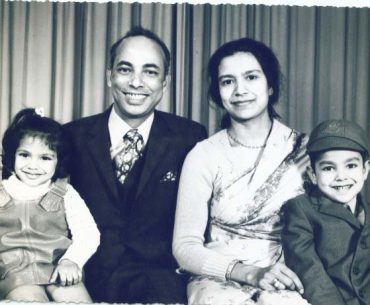

* The featured image includes previous competition entrants, winners and photographs from the archive collection.

The Prizes

- Three overall winners will each receive £100. They will also be included in exciting new Everyday Muslim projects that could see them featured in a publication, exhibition (National partner TBC) documentary and subsequent collaborative ventures.

- Ten exceptional entrants will also be broadcast live at our virtual awards ceremony and included in future Everyday Muslim projects.

About the Competition

- The competition will open at noon (GMT) on November 24th 2022.

- All entries must be received by noon (GMT) on March 17th 2023.

- Open to ALL global entrants; however, images are to depict Muslim ‘everyday life’ in the UK or Ireland.

- Entrants cannot be related to any persons organising and/or judging the competition.

- The competition is free to enter.

- Submitting an image to the competition means you agree to accept the competition rules, terms and conditions.

Rules, Terms and Conditions

Submitting Entries

- The competition will open at noon (GMT) on November 21st, 2022.

- All entries must be received by 23:59 (GMT) on February 19th 2023.

- Entries can only be submitted through the online submission platform.

- Submissions must be in a digital jpeg (JPG) or TIFF format and at least 5mb in size.

- People under 18 must have consent from a parent or legal guardian before submitting Photo(s) into the prize and by entering are confirming that they have permission. The parent’s email and details must be submitted.

- Each Photo(s) can only be entered once into the competition.

- Each Photo(s) can only be entered into one category. *Khizra Foundation reserves the right to move any Photo(s) into a different category if it feels that is more appropriate.

- Each Photo will be judged individually and must work as a standalone Photo.

- Photo(s) that have won or been shortlisted previously in the prize cannot be entered again.

- Any works initially commissioned by Khizra Foundation are not eligible for submission.

- Photo(s) that have been previously published can be entered into the prize. Except if; Photo(s) have won any previous award(s)in any other competition(s) whatsoever, and/or Photo(s) that have been previously used, or are intended to be used, for any kind of commercial purposes, must not be submitted. Any Photo(s) submitted contrary to the preceding will be automatically disqualified from the entire Competition without further notice.

- Watermarks, names or other information identifying the Photo(s) creator or copyright holder, their representative, or any institutional affiliations or publications, must not be visible in the Photo(s) themselves. This information will be asked for as part of the submission process.

- All Photo(s) must be accompanied by accurate captions containing all the information described in the guidance provided during the submission process. All captions and any related information must be submitted in English.

- Khizra Foundation reserves the right to disqualify any submissions not of acceptable quality or where the accompanying caption is insufficient, unclear or untrue.

- Khizra Foundation’s judging panel has the right, at its absolute discretion, to turn down or reject any photo(s) or Submission(s) without having to give any notice or explanation to the relevant Participant.

- Khizra Foundation’s judging panel’s decision is final and binding on all Participants concerning all matters relating to the Competition.

Copyright and Permissions

- For the purpose of this section on copyright and permissions, Photo(s) includes Photo(s) any written captions or other text submitted with the Photo(s).

- The entrant or their representative submitting Photo(s) on their behalf, must be the copyright holder or have permission from the copyright holder to submit Photo(s) to the Competition under the terms and conditions specified here.

- Copyright holders retain copyright in their work.

- Copyright holders of all submissions grant to Khizra Foundation a non-exclusive, royalty-free worldwide, irrevocable right to copy, adapt, distribute, perform and use in whole or part their submitted Photo(s) in any media (including social media, online and print) in connection with the operation, promotion and/or description of the prize, on a perpetual basis in connection with the prize (as described above) together with use for merchandising purposes and for any uses connected with Everyday Muslim’s collecting, documenting, education, promotion and archive related purposes. When using a Photo(s), Khizra Foundation will reference the story or topic to which it relates wherever it is reasonably practical to do so.

- All photographs entered into the competition will be given the opportunity to be entered into the Everyday Muslim Archive collection on the entry form.

- Copyright holders will be credited when their Photo(s) is/are used. Any failure to provide such credit shall not be deemed a breach as long as Khizra Foundation makes reasonable efforts to rectify such negligence within a reasonable period from the date of notice of such failure.

- The entrant or their representative submitting Photo(s) on the behalf warrants they have all third-party permissions and releases necessary to have taken the Photo(s) and to publish the Photo(s), including all the relevant personal information shared with Khizra Foundation. The entrant will provide details to confirm that these permissions are in place if requested by Khizra Foundation to do so. Although, submitted entries will be assumed to have these in place as already mentioned.

- The entrant or their representative submitting Photo(s) on their behalf warrants that any material submitted is their own original work and does not infringe the copyright or any other rights of any third party.

Judging and Prizes

- All judging decisions are final, and no correspondence will be entered into over these.

- If a prize winner or shortlisted entrant cannot be contacted within seven days of the judges’ decision, Khizra Foundation reserves the right to award the prize to another entrant.

- Prizes are as stated at the time of submission.

- Khizra Foundation reserves the right to exclude an entry and revoke any prize made, at any time, in the event of a breach of these terms and conditions by the relevant entrant.

Liability

- Insofar as is permitted by law, Khizra Foundation will not in any circumstances be responsible or liable to compensate any entrant or accept any liability for any incomplete, late, misdirected, stolen, lost or damaged submissions arising from participation in the Competition.

- If any material provided by an entrant infringes the copyright or any third-party rights, then the entrant will take full responsibility for this.

- These terms and conditions and any dispute or claim arising out of or in connection with its subject matter or formation (including non-contractual disputes or claims) shall be governed by and construed according to the law of England and Wales.

- The terms set out here are binding, and Khizra Foundation reserves the right to refuse or exclude any entries at its discretion.

- Khizra Foundation reserves the right at its sole discretion to change the terms and conditions, make changes to the timetable, prizes awarded or other aspects of the Competition. If you maintain your Photo(s) in the Competition after the publication of these changes, you agree to be bound by those changes.

- Khizra Foundation is not responsible for any misuse of Photo(s) by third parties.

- If for any reason, the Competition is not capable of being conducted as anticipated due to computer virus, bugs, tampering, unauthorised intervention, fraud, technical failures, or any other causes beyond the control of Khizra Foundation, which corrupt or affect the administration, security, fairness, integrity or proper conduct of the Competition, Khizra Foundation reserves the right at its sole discretion to cancel, terminate, modify or suspend the Competition as deemed appropriate, disqualify any Participant, and/or select winners from all eligible Photo(s) submitted before the termination, cancellation, modification or suspension. Khizra Foundation reserves the right to correct any typographical, printing, computer programming or operating errors at any time.

*Everyday Muslim is a project undertaken by Khizra Foundation. It can also be known as the Everyday Muslim Heritage and Archive Initiative (EMHAI), Everyday Muslim or the Everyday Muslim project.