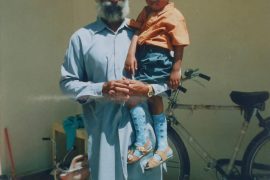

My great-grandma lived through Partition; her name was Mansur Faatimah Shah. I grew up listening to many stories of her endurance and bravery, about how she made her journey to Pakistan during the violence and disorder of Partition. She was born in pre-partition India. She lived in Kapoorthala village, Sheikpura Bohoi in the state of Riasat, current day India, with her family, the Kazi family, who earned their name due to their profession as judges during the Mughal empire. By the time my great-grandma was born, her family were agriculturalists. Their ancestral lands included a large portion gifted to them by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan for educating his children Dara and Aurangzeb. They lived a life of happiness.

My great-grandma lived through Partition; her name was Mansur Faatimah Shah. I grew up listening to many stories of her endurance and bravery, about how she made her journey to Pakistan during the violence and disorder of Partition. She was born in pre-partition India. She lived in Kapoorthala village, Sheikpura Bohoi in the state of Riasat, current day India, with her family, the Kazi family, who earned their name due to their profession as judges during the Mughal empire. By the time my great-grandma was born, her family were agriculturalists. Their ancestral lands included a large portion gifted to them by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan for educating his children Dara and Aurangzeb. They lived a life of happiness.

She was married in 1945 to a man called Ali Ahmed Shah, who lived in Sultan Shah, which straddled India and modern-day Pakistan, an area in Punjab. One of my favourite stories of her youth is that her father borrowed an elephant from the raja at the time to ride during her wedding procession. In 1947 she was pregnant with her first child, and according to tradition at the time, she returned to her family home in Kapporthala village to see out her pregnancy there. In August, while she was still with her family in Kapporthala and five months pregnant, partition occurred, and violence broke out. Her father, due to his status in the village in dealing with local legal cases, was the target of a lot of anger, and therefore, as a Muslim in a now Hindu majority India that was in turmoil, was killed, as was his wife Hayat Bibi, my great grandma’s mother and her two sisters.

While we don’t know the whole story of how she was the only survivor in her immediate family, my grandfather’s family believe that her father’s friend, a Hindu man called Ram Ashra, took her to the train station. He also found a young boy called Fakir Hussain, my great grandma’s nephew, who we learn some of her story from, hiding in the fields of their wider village area. He also took Fakir Hussain to the train station, where my great-grandma was. They boarded a cargo train together. As my grandma was heavily pregnant, she needed assistance to board the train, a man named Ismail, who she often spoke about due to his kindness, bent down so she could use his back to leverage herself onto the train. They hid in empty coal boxes to avoid detection. The train, at one point, was intercepted by mobs, and many of the people on it were violently murdered. The police arrived before the violence reached my great-grandmother’s cabin, so she was spared.

Ram Ashra was tasked with the safekeeping of the family’s gold and jewels, which we know he buried in the ground, and which no one ever returned to recoup. When I think about it, this wealth was left in the blood-soaked mother land, which was ripped apart to give birth to a new country and all of its trauma. The land reminds me of my great-grandma and all the sadness she felt and saw as a pregnant woman herself. She was heavy with the promise of a new life and the burden and sorrow of the one that was violently taken from her.

The train eventually came to Lahore, and as they reached safety, they discovered other nieces and nephews of my great grandma and Fakir Hussain’s siblings. It is likely the children were given safe passage by someone to get to the train station. Fakir Hussain was reunited with four of his older sisters – Mahmooda, Nasir, Naseem and Zara, as well as his cousins Ishrar, Jaaji and Sajad. My great-grandma described the hunger she felt during her tumultuous journey, she was given a plate of roti, pickle ‘achar’ and cool water when she arrived at the station, and despite her upbringing of wealth and luxury, she described it as the best meal she’d ever had. What she discovered was her husband’s family had come to the train station every day in anticipation of her arrival. I can only imagine what a relief it was for all of them on the day she did finally arrive.

In the aftermath, she was traumatised by the horrific events that she witnessed and endured. When I spoke to my great Aunt, Zia Shah, my great-grandmother’s third daughter, she mentioned that her sisters’ children, who had also reached safety with her, provided some comfort and solace from what had unfolded.

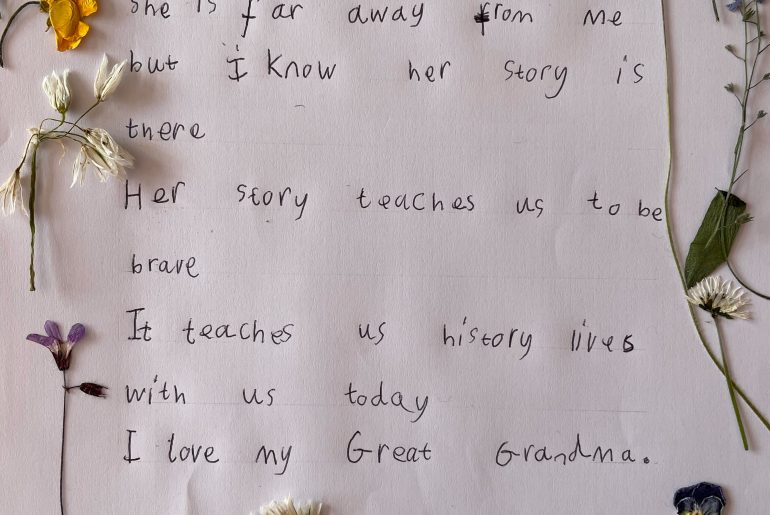

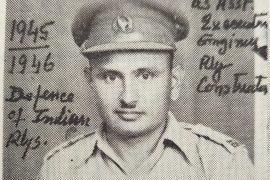

They all settled in an area called Zafar Ke in Punjab. Eventually, the government repatriated a portion of their expansive lands within the newly formed Pakistan as recompense. In December, after this traumatic and life-shattering event where she lost everything she knew, she gave birth to a healthy young boy called Hassan Shah, my grandfather’s oldest brother. Her early life in Pakistan was spent on her husband’s ancestral lands in Sultan Shah. She moved to the city of Kasur, Punjab, along the Pakistani and Indian border, to ensure her children had the best possible education. This included her youngest son, my own paternal grandfather Khalid. Their home in Kasur was originally a converted stable that they owned. She went on to have six children, one of whom died in infancy, and two sons. She lived till she was in her eighties.

My paternal grandma Qouasar lived in London; her mother went to Pakistan in 1974 in search of her husband and was recommended a young law student, my grandfather, Khalid. They married in 1976 after my great-grandma met my grandmother Qousar. Her first question was whether my grandma could make butter. My grandma answered, regrettably, no. They went on to have four children, the third of which is my dad, Adnan. My grandma Qousar lived for some time in Pakistan after she got married, and she heard these stories of my great-grandma’s bravery. My grandma also told me that my great grandma was a herbalist; she had a great book with lots of natural medicines and remedies. One entry my grandma told me I thought was very interesting because it used shed snake skin, ground and mixed with makkan (butter). My great aunts would return home to my great grandma whenever they had a scar to apply some of this balm to speed up healing.

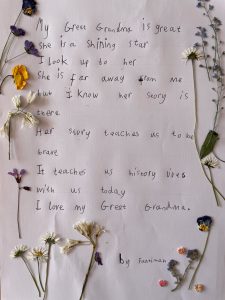

Growing up, these stories were valuable because they helped me to piece together my own story as a young British Pakistani Muslim. It is important to me to document and record this so her story is heard and not lost forever. As my grandma has dementia, the stories she tells me about her mother-in-law are losing detail and sequence. As the great Fakir Hussain also gets older, I worry I will never learn things about her life. I feel a responsibility to write these stories down, so the history of partition can be seen in the way my great grandma, the true hero of the story, experienced it, and not just through the eyes of the powerful decision makers – who didn’t face the consequences of their actions.

Khadijah

Comments are closed.