Sabrina Abdihakim, a Muslim Somali residing in Northwest London, talks about her experiences growing up in London as a child and a young adult. Sabrina is very close to her family and comes from a small Somali household. While her mother was away in India, their grandmother raised Sabrina and her siblings. In many Somali homes, it was extremely common for the grandmother to communicate with their grandchildren in Somali, which was the case for Sabrina. Many young Somalis in Britain are first-generation Somalis; thus, they naturally speak to their elders in their native dialect. Although Sabrina states that as the generation goes on, the mother tongue becomes less common, ‘‘I speak the best Somali, the youngest doesn’t know one word’’.

She discusses her family background and immigration narrative. Her grandmother, a woman with five children, all emigrated, and Sabrina’s mother moved in that direction, where she eventually met her father. The late 1990s were a challenging time for the Somali people as the civil war significantly impacted the contemporary Somali people’s lives. Many struggled, but Alhamdulillah pulled through and gave their children and families a better life. Moreover, during and after the Somali Civil War, a significant number of Somalis were dispersed all over the world.

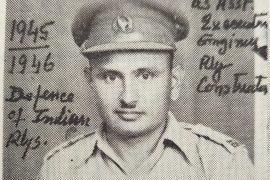

Street scene from Barawe, Somalia

Street scene from Barawe, Somalia

Regarding friendships, Sabrina didn’t have many Somali friends growing up and realised how much she was losing out on until she reached year 10. She had never intended not to make Somali friends; they just hadn’t crossed her way. She was separated from her people, the majority of whom were in the section she was not in, by her school’s division of pupils into sections A and B. Education played a role throughout Sabrina’s life. She attended primary, secondary, and then college before attending university, where she majored in psychology. She furthered her studies by doing amaster’ss in human resources management. Although pursuing psychology as her undergraduate, she felt like her psychology degree did not get her far.

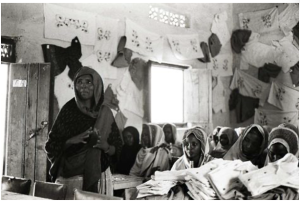

Second-year students in Mogadishu in 1977

While Sabrina had attended a madrasah typical for many Somali children, the focus had been on learning the Quran and being proficient in it, not on understanding the deen. When discussing Sabrina’s experience at the madrasah, she ‘‘loved them’’ but states that that experience was not universal. She talks about her sibling’s experience with the madrasah,’ they’d get beaten up, which was sad’’. This impacted Sabrina, who would stay up late at night to ensure she was ready to face the day without being punished. The authorities of these madrasahs would use wires to hit their students and believed this was the correct way to teach the deen to young children. As Sabrina got older, she learnt the religion independently and with the help of influences around her. She had started making more Muslim friends, which positively impacted her. She took it upon herself to go to bookstores and read and learn more about her religion. She also watched lectures online, which are beneficial for improvingessayss Muslim life. These lectures offer guidance that madrasahs, which many young children had previously attended, did not. Sabrina felt like she had a rebirth as a new Muslim; growing up in her Somali household, she states,’‘They teach you no alcohol, no sex, no cigarette’’. The older generation had passed down the teaching of avoiding the bigger sins but stopped there and did not go further.

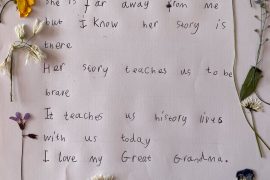

A picture from a sewing class from the 1970s

When it came to Ramadan in Sabrina’s household, it had been a special and enjoyable moment for her and her family. Her household was constantly busy, surrounded by family and friends, and togetherness played an essential role during Ramadan. A natural community of Muslims is built and brought together during this time. Islam plays a significant role in Sabrina’s life as an adult; it shapes who she is and how she lives her life. She states that there is still passing judgement within the Muslim community as ‘Everyone’s judging each other’. You must always present yourself as someone considering the deen in this environment since judgement is severe, especially when using social media. According to Sabrina, the influence of social media has made it easier for people to judge others. This judgement comes not only from the Muslim community but also from non-Muslims. Islamophobia continues; Sabrina states that for a long time, she had not received jobs due to her hijab, and she had been encouraged to take it off; however, Sabrina had seen the wrong. Muslims should not let go of something that’s part of them to fit into the Western standard. When she did settle into the workplace, she still felt restricted, particularly with her clothing ‘I used to wear an abaya, and now I feel like where I work, I can’t. Many Muslims who live in the West are encouraged to alter their lifestyles, which causes them challenges and difficulties.

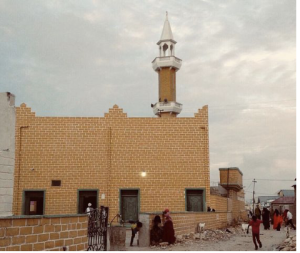

Masjid Fadumo in Bosaso

Furthermore, due to feeling alienated from the Muslim community at one point in her life, Sabrina wasn’t always the biggest fan of Muslims. Growing up, she had observed that Arabs and Asians were less accepting of others and felt inferior. This is a problem in the Muslim community, where anti-blackness is firmly ingrained in many ethnicities and cultures. Navigating and living in a culture where those from and outside your community continuously denigrate you is complicated. Sabrina has always seen herself as her religion first, then her ethnicity, Muslim, then Somali. Her identity as British would only be included in the forms and documents; she does not identify with it daily. Yet, when she contrasts herself with Somalis back home, she feels a displacement in the community, and her Britishness does come into play. Also, Sabrina discusses how unjust it is that white people have more opportunities than black people. You might be the most qualified candidate at the job interview, but because of prejudice and discrimination, the white candidate you were up against was hired. Sabrina understands how frustrating it may be, but she also understands that all you can do is keep a good outlook and hope the next opportunity comes your way.

Author and Researcher – Idsam Egal

This blog was based on the oral history interview by Sabrina Abdihakim for the Everyday Muslim archive projec’ ‘ The Heritage Story of Black Muslims in Londo’.’

Comments are closed.