Karim Khan is a playwright and screenwriter from Oxford. His newest play, Before the Millennium, is showing at The Old Fire Station in December. Written by Ivor Starkey, based on Karim’s oral history account from our upcoming Muslims in Oxford Archive collection, in partnership with The Community History Hub at the History Faculty, Oxford University.

As he grew and explored the rest of the city, Karim describes the university as one of the oldest and most prestigious in the world, as being like another world or a parallel universe, set apart from the rest of the city. This part of the city feels unreachable and exclusive, and it was only when he was invited on an open day by one of his teachers that Karim even contemplated the idea of studying there. He considered applying to Oxford for English; yet would later go to University College London for the same course.

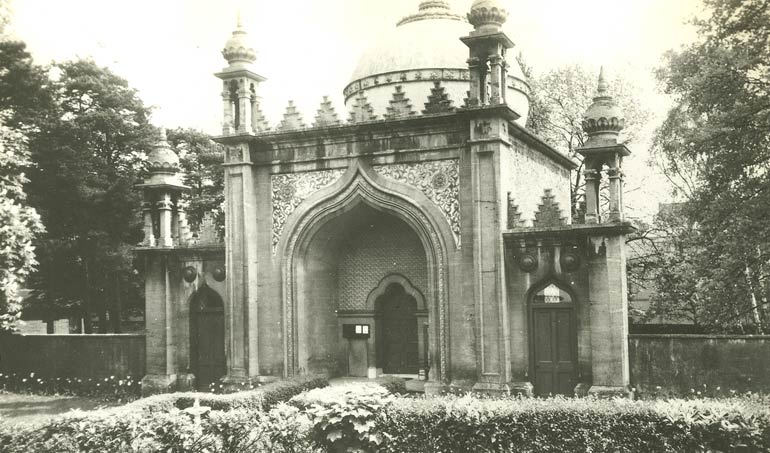

Despite often feeling ill at ease, there was a strong sense of community amongst Muslims in Oxford that Karim could draw on. The Bath Street Mosque, although small and in a permanent state of construction, was entirely self-funded by its congregation. Donations would come in, contributions for a new carpet or roof: whatever was needed the bucket would be passed round.

Amongst the immigrant population in Oxford, Karim says, there was a strong group feeling, a support system which linked migrants in similar positions. As in a large extended family, there was an emphasis and expectation of showing up for others, especially in visiting members of the community during sickness and after death. There was a camaraderie between the various mosques in Oxford; they were all in the same boat. Yet still it was hard to live as a Muslim in Oxford he mentions the lack of halal butchers in the city.

Once in secondary Karim would go every Sunday to a drama club in a local village hall. Drama and acting led on to him pursuing film and filmmaking, supported by grassroots projects such as Film Oxford, who invited him to use their equipment and participate in their film festival for young people, Summer Screen. After studying English at UCL, he would go on to study MA Film and TV Studies, whilst also taking the opportunity to write and build up his portfolio. The following year he enrolled at the National Film and Television School to pursue his dream.

This was the beginning of his career, but entering the theatre or film industry as a Muslim was daunting. He had little experience of going to see plays, and Theatre itself came across to Karim as an overly intellectualised industry for middle-class Shakespeare snobs.

Yet, despite this, he recognises a new movement of Muslim writers and producers, who are each inspiring and encouraging one another. As one play by a Muslim producer sees success, more and more up and coming writers feel that they can write a play or television series. This is an opportunity for Muslims to direct their image, to represent themselves and to lay out a more authentic portrayal of their experiences and lives in the Modern United Kingdom.

Oxford, Karim’s city, has inspired his own work and writings. In Karim’s play, Brown Boys Swim, the city appears almost as a character in itself. It follows two brown Muslim Oxonians – Kash and Mohsen – growing up, and grappling with their both their families’ expectations and their own faith. The play is a way for Karim to present his identity, background and experiences albeit to an overwhelmingly white, middle class, London audience – so that others can engage and connect with it.

Kerim tells us that he has often felt compelled to lay out a certain narrative in his work, because of his Muslim, migrant heritage. There is a tendency for Muslim writers or writers of immigrant background to write solely about trauma and struggle. But this is to make exotic your own culture and history, to try and make it compatible or palatable for an uncomprehending audience. He wants joyous stories, stories that are written on his own terms. “I’ve seen so many plays about Prevent now, and I want to see Muslim writers feel like they don’t need to respond to that provocation anymore”.

But, at the same time, he knows that he cannot tell every Muslim story. With a rising wave of vitriol against Muslims, it is more important than ever for Muslims to write and direct their lives, because, as he tells us, even “representing your reality as a Muslim in itself is political”.

Author: Ivor Starkey