It’s not often that the label being a ‘rebel’ is associated with a force for good but with Saida Sherif it was precisely her outgoing ‘fiery temper’, her independence, and a willingness to stand out from the crowd that saw her significant achievements as a female Muslim migrant to Britain in the 1950s.

Born in Delhi 1932, Saida was the second youngest after five brothers and a younger sister. This family structure with Saida considering herself as a self-confessed tomboy, was the beginning of the influences on her life leading to her multiple careers and accomplishments. Saida was from an elite and educated background with her father one of the few Muslims to have graduated from university and her grandfather held the lofty position as the Chief Muslim judge of Saharanpur. The women in her family, including her grandmother, were considered well cultured people and were well educated in Islam and poetry. They often performed poetry to the family as a form of amusement and theatre in the privacy of the home.

It was at school that Saida’s rebellious streak became truly evident. Like many other ‘radical writers’ before her, Saida received an education but was fortunate to receive it at a school where she found herself in a class of only two girls and the remainder boys, underscoring her unique position as a Muslim girl in 1930/40’s India. It was in that environment that Saida gained the confidence to speak in front of others and the ability to express her thoughts and opinions.

1947 Partition and Relocation

Saida’s idyllic early childhood and education contrasted with her later experiences which were punctuated with the violence and upheaval of partition. From the age of fourteen, Saida’s life was disrupted with curfews, gunfire and screams in the middle of the night. This eventually resulted in the trauma of being forcibly removed from her home, with Saida’s baby niece being thrown from her pram.

From this point Saida’s transient life began moving from Delhi to Bombay, to Karachi and eventually to London in 1948. Saida experienced the anguish of leaving her childhood home and friends, and the separation of her brother during the events of partition. The violence in India’s past on Saida’s family, such as the 1857 mutiny, recalled vividly by her grandmother, coupled with the upheaval of the 1947 partition, left profound marks on Saida that would influence her future path.

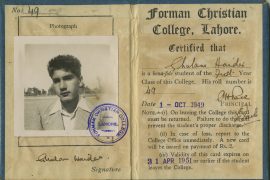

After her marriage in 1948, Saida moved between London and Switzerland, where she yet again pushed the boundaries in education by studying Journalism at Bedford College Regents Park. In 1950 Saida was the only woman to have studied journalism at her college, an impressive achievement in its own right and despite the discouragement of the college who argued ‘This is not a woman’s job’ Saida’s tenacious and rebellious spirit saw her continue her course and actively pushed the boundaries not just for Muslim migrant women in Britain but for all women.

Teaching and The Start of Saida’s Humanitarian Calling

Saida juggled marriage and family life with her three children with multiple occupations; each vocation intermingled and became a reason for her next calling. However, It was her career as a teacher that would be her gateway to philanthropy and as a writer. Saida’s ability to lead and affinity for speaking in public saw her embark on her first

significant career as a teacher in Britain and abroad. Whilst teaching at the International Minarah School in Jeddah, Saida found herself drawing closer to her faith – Islam, through teaching Islamic Studies. Her encounters with her Palestinian neighbours and their stories of anguish, coupled with her self-realisation of the Islamic importance of helping the needy, led to her true calling in life as a humanitarian and charity worker. Once back in Britain, Saida set about raising awareness for the Palestinian cause in an inclusive way and created interfaith workshops to educate on the cause.

Working in a Warzone

As well as her faith, Saida was inspired by her own children to continue her involvement with humanitarian and charity work. The anxious appeal of her daughter about the war in Bosnia between 1992-1995 led to her asking, “Mummy, why don’t you go there? You are so upset here”. This resulted in Saida undertaking one of her most dangerous but worthwhile missions in the Bosnian warzone.

In Split, Croatia, Saida visited many refugee camps where women and children were kept under barbed wire and with a group of American aid workers set about taking them to a place of safety, ensuring they had food and support.

Many of the refugees were Muslims, and during this time, practising Islam publicly was dangerous. Saida vividly described the threat from soldiers “There have been soldiers coming in here; they have said that they will bomb my place if I keep the terrorist, the Muslim terrorist, in the building because they heard you doing adhaan’. Despite this, Saida continued to pray in secret and silence with the children; such was the show of determination of not only Saida but also the child refugees who were unwavering in their faith.

A second trip to Bosnia in 1993 saw Saida directly in the warzone where she was witness to bombs being thrown, women being killed and the screams of children who had lost their parents. It was a dangerous and traumatic experience, and it takes a person of immense faith and strength to be able to selflessly help others during a perilous state of war, especially as a mother with a family of her own.

After the Bosnian War, Saida continued her humanitarian work in further war-stricken countries, including Kosovo, Albania, and Afghanistan. Saida describes herself as being ‘fearless’ and with no fear of the danger she faced, trusting her fate with her faith.

During the pockets of time in the middle of the night in the Bosnian warzone when she couldn’t sleep, Saida poured out her feelings and the pain of those around her into her poetry which became an outlet of the emotions and sights she experienced and witnessed around her. Many of Saida’s poems made their way to a published book called Kasak – meaning ‘a kind of pain you feel in your heart’, which aptly sums up Saida; despite her fearless nature, she never allowed her heart to become desensitised to her emotions and those around her. Her poetry book Kasak and her memoirs Sparks of Fire would become an outlet for those emotions and thoughts.

Saida’s story is one of female heroism, selflessness, and faith. It is a story which is not just exclusive to Muslim women but ones that serve as an inspirational story for all and demonstrate how past experiences and traumas can be turned into a force for good. Saida’s legacy already lives on through her children, who continue her humanitarian work, but through her books and her interview with Everyday Muslim in 2017, which has been retold here, Saida’s legacy can continue to inspire countless more.

Authored by Tabassum Hawa from an interview for the Everyday Muslim Archive in 2017.

Comments are closed.