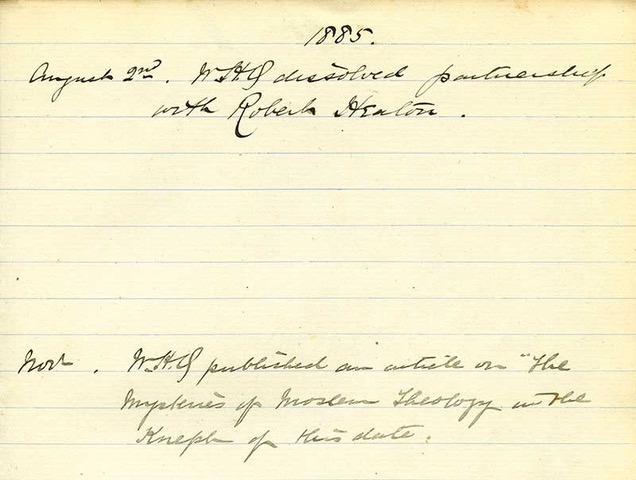

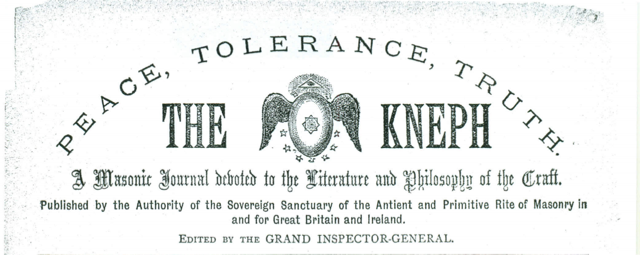

Since the publication of Prof. Ron Geaves’s commendable book, Islam in Victorian Britain, in 2010, in which he noted the existence of “The Mysteries of Moslem Theology”,[1] based on a handwritten chronicle of Quilliam’s earlier life of unknown provenance, Prof. Patrick D. Bowen could not source the article despite searching for it. Years went by and the article appeared to have been lost. When the Abdullah Quilliam Society recently re-uploaded the chronicle of William Henry Quilliam,[2] I got a chance to see this reference for the first time. The second entry for the year 1885 notes,

“Nov. W.H.Q published an article on “The Mysteries of Moslem Theology in the Kneph of this date.”

No date was written but the name of the journal – Kneph – was. With that in hand, I decided to search the University of Manchester archives and on the 9th October 2019, I found the article just before 10am. Without question, I was elated. What this discovery proved, to me at least, is that the dairy is indeed trustworthy and was written by someone close to Abdullah Quilliam, or even Quilliam himself. Then I started to double-check each claim the diary makes with external evidence (mainly newspapers) and realised further that many of the claims it makes are indeed verifiable from an external source.

Just a year prior to the publication of “Mysteries”, Quilliam was at the Gibraltar Straits, where his eyes set upon a group of Hajjis – pilgrims – praying on a steamer. That was enough to get his attention and arouse his curiosity. In the words of a contemporary, they introduced Quilliam to some rudiments of Islamic theology and he even memorised few chapters of the Qur’an.[3] Nothing much is known about Quilliam between 1884 till 2nd August 1885 (the day he finished writing the article though it was published in November 1885) except his sharp rise as a lawyer when he defended the then notorious “Black Doctor” and “Quack Doctor” Etheus de Tomanzie and defended the two Irish bombers James G. Cunningham and Patrick Henehan, among other legal work.[4]

Coming to the article itself, it seems, from the first glance, to be a work produced solely by Quilliam after further home study and reflection over the previous year after his return from Gibraltar. Once you begin reading it, you realise there are many garbled transliterated Arabic or even Turkish terms, such as “Jdjhay-ummeth”, “yatebs” and “kaims”. Then, right at the bottom, Quilliam lists his sources. After I rummaged through those sources, hoping to find out what these words might mean, I realised instead that the vast majority of the article was ‘borrowed’ from three main sources that Quilliam cited: John Reynell Morell’s Turkey, Past and Present; Washington Irving’s Life of Mahomet; and George Sale’s translation of and commentary on the Koran. Not only were chunks of passages “borrowed” from these three sources but, even at times, their structure as well. Besides two tiny paragraphs near the end, not a single paragraph is Quilliam’s own prose. All of them are either directly copied verbatim or paraphrased. Even Morrel and Irving copied Sale, and, in this article, Quilliam followed the tradition.

This begs the question, why did Quilliam feel the need to copy? Was it crude plagiarism? Well not of the most egregious kind because, as noted above, Quilliam mentions these three sources among others that he believed would be conducive to learning about Islam. Doubtlessly, this list of sources is also direct evidence in reconstructing Quilliam’s earliest research on Islam and how this shaped his early thinking. Does it also reflect his very basic knowledge of Islam at the time, and, therefore, a lack of intellectual confidence shown by Quilliam, in copying from these three sources to avoid errors (and in fact inadvertently reproducing mistakes in these same sources) to present a credible article in a journal? Probably.

It should also be noted that copying older sources without referencing was a common-enough practice at the time. Many encyclopaedias, including authors such as Morrel and Irving, directly copied George Sale’s translation and commentary on the Koran since it was viewed as the standard work on Islam.[5] In this light, it would be unfair to judge Quilliam for a commonplace Victorian practice through the lens of strict, contemporary standards against plagiarism.

Comparing “Mysteries” (1885) with his first book, The Faith of Islam (1889), there is a clear and distinct change in Quilliam’s understanding of Islam. In short, it was maturing. Gone are the verbatim unattributed sentences; quotations are referenced in the latter work. In addition, Quilliam had realised that Morrel was untrustworthy on the history of Islam, thus he no longer referenced him. By 1895, when he published Studies in Islam: A Collection of Essays, Quilliam’s range of historical references had profoundly changed: the essays ranged from the poet Firdausi to science to the “Moorish conquest of Spain”.

In presenting this first essay by Quilliam on Islam, I have kept the spelling the same as it appears in the original. All the numbered references in square brackets are mine whilst the letters in round brackets are Quilliam’s. Every time I reference a paragraph or sentence, I compare it to the original source that I have evidence Quilliam borrowed from. Thus, under the heading of “References and Notes”, all the notes are by me.

The Mysteries of Moslem Theology

To form anything like a correct judgement of the Moslem system of theology and the rites in connection therewith, it becomes necessary to examine briefly into the state of Arabia prior to the advent of Mahomet.[6] Before the birth of the prophet the Arabs possessed divers religions; some were Christians (a), others Jews (b), others fire and star worshippers (c), and many idolaters (d), others an immense idol of paste (e), and one tribe blocks of stone (f).[7]

Among the djahylia (or idolater) every head of a family had protecting deities in his tent or house, which he saluted on either entering or issuing from the habitation [8]. In the kaaba of Mecca and its precincts were placed, moreover, 360 idols each of whom presided over one of the days of the Arab year [9]. The Moslems trace the history of the worship of idols as resulting from the grieving of the living for the dead, and ascribe its origin to Jaouk and Nesrane, two of the sons of Adam, forming a copper image of their deceased brother Jakout to remind them constantly of the dead. When the great Creator called them to Himself in turn, their children did the same thing for them they had done for their brother, and gradually the following generations confounded in a common worship their ancestors and the true God, and lost at length the traces and traditions of the primitive and true religion.[10]

he history of the faith of Islam commences with the Hegira (the flight) of Mahomet in the year 622 of the Christian era. It is not for us here to enter into the dispute as to whether the prophet of Islam was inspired of God, or merely a deluded man, or an arch-cunning impostor; but without venturing to dissect the mysteries of instinct and inspiration it will suffice to say that the Arabian seer was evidently gifted with a sublime genius, and was actuated by divine principles. He regarded himself as an ambassador of heaven, who was sent to his people to lead them into the knowledge of the only true God; and he was convinced that the work in which his doctrines were inscribed was a book written from and for all eternity, and in accordance with this conviction the prophet required unlimited faith and obedience to the Koran.[11]

The broad principles and convictions that impressed the mind of the Moslem prophet are inscribed on almost every page of the book and fall under the following heads: —

The doctrine of one only God.

The immortality of the soul.

The duty of man and thankfulness to his all-wise and beneficent Creator,—not to regard afflictions or external prosperity, if the object is to convert men to God; to make use of reason, which has been lent to us by God, to acquire knowledge, and to honour wisdom and science, and in general to provide for well-being and honour in this world and the next.[12]

In many, in fact in most points, the Moslem system is analogous to the theology entertained by Unitarian Christians.[13]

The sacred book of the followers of Islam is the Koran which all Moslems believe to be a book of divine revelation.

According to their creed a book was treasured up in the seventh heaven, and had existed there from all eternity, in which were written down all the decrees of God, and all events, past, present, and the future. Transcripts from these tablets of the divine will were brought down to the lowest heaven by the angel Gabriel, and by him revealed to Mahomet. As these are the direct words of God, they were all spoken in the first person.[14]

Besides the Koran, a number of precepts and apologues which casually fell from the lips of Mahomet were collected after his death by his disciples, and these are transcribed in a book called by some the “Hadiff”, by others the “Sunneth,” but generally the “Sonna.”

This work is held by one sect of the Moslems, the Sonnites, as equally sacred with the Koran; the other great sect, the Schiites, reject it as apocryphal.[15]

A third work deeply reverenced by the Moslems is the “Jdjhay-ummeth”, or the explanations and decisions of the most eminent disciples of Mahomet, especially the first four Caliphs.[16]

Another work read with reverence is the “Kiyas,” which consists of a collection of the canonical decisions of the Imams or teachers of the first centuries after the Hegira.[17]

The religion of Islam is divided into two parts; Faith and Practice.

Faith is divided under six heads, or articles.

1st, Faith in God; 2nd, Faith in God’s angels; 3rd, in His scriptures or Koran; 4th, in His prophets; 5th, in the resurrection and final judgement; 6th, in predestinations. Of these we will now briefly treat in their order.[18]

FAITH IN GOD. —This is the belief that there is, ever was, and always will be, one only God, the Creator and ruler of all things, who is single, immutable, omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent, incomparable, all merciful and eternal. This unity of God is specifically and strongly argued in contradistinction to the Trinity of the Christians. It is designated in the “El Chehada” or Moslem creed by raising one finger (the forefinger of the right hand) towards heaven and exclaiming, “La il Alla il Allah!” There is no God but God, to which is added “Mohamed resoul Allah!” Mahomet is the prophet of God.[19]

FAITH IN ANGELS. —The beautiful doctrine of angels or ministering spirits, one of the most ancient and universal of oriental creeds, is interwoven through the Islam system; and he who denies their existence, their purity, or hates any of them, or asserts any distinction of sex among them, is deemed an infidel (g).[20]

These angels are believed to have pure and subtle bodies, created of fire (h); they neither eat nor drink, nor propagate their species; they have various forms and offices; some adoring God in different postures, others singing praises to Him, or interceding for mankind; some are employed in writing down the actions of men, and others in carting the throne of God and other holy services. [21]

The four principal angels are Gabriel, Michael, Azraël and Israfil.[22]

FAITH IN THE HOLY SCRIPTURES: —The principal of these is the Koran, to which we have already alluded; but in addition to this Moslems believe that God in divers ages of the world, gave revelations of His will in writing to several prophets, the whole and every word of which it is absolutely necessary for a good Moslem to believe. The number of these sacred books was 104; of which 10 were given to Adam, 50 to Seth, 30 to Edris or Enoch, 10 to Abraham; and the other 4[23] are the “Thourat,” or “Pentateuch, which was delivered to Sidna Moussa (Moses); the “Zabour,” or Psalms, to Sidna Daoud (David); the “Lendjil,” or Gospels, to Sidna Aissa (Christ), and the Koran to Sidna Mahommed (Mahomet),[24] which last being the seal of the prophets, those revelations are now closed, and no more are to be expected. All these divine books except the four last are now entirely lost and their contents unknown, though the Sabians have several books which they attribute to some of the antediluvian prophets. And of the four still extant the Pentateuch, Psalms, and Gospels have undergone so many alterations and corruptions, that though there may possibly be some part of the true word of God therein, yet no credit is to be given to the present copies in the hands of the Jews and Christians.[25]

FAITH IN GOD’S PROPHETS: —The number of prophets which from time to time have been sent by God into the world, amounts to 224,000, among whom 313 were apostles, sent with specials commissions to reclaim mankind from infidelity and superstition : but only six are super-eminent as having brought new laws and dispensations upon earth, each successfully abrogating those previously received wherever they varied or were contradictory; these were Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Christ and Mahomet. All the prophets in general are believed to have been free from great sins and errors of consequence, and professors of one and the same religion, that is Islam, notwithstanding the slightly different laws and institutions which they observed.[26]

FAITH IN THE RESURRECTION OF FINAL JUDGEMENT: —The Moslem ideas on this subject are so similar to that of the Christian belief, blended with the notions of the Arabian Jews, that it would be a useless expenditure of space for us to give them in detail.[27]

It is well to observe however that the place of punishment is divided into 7 stages or floors, for different classes of delinquents,[28] and the future place of happiness is called “Jannat,” or garden, corresponding to the Greek word Paradise.[29]

FAITH IN PREDESTINATION: —This sixth and last great point of Moslem faith is the belief in God’s absolute decree and predestination of good or evil, the orthodox being that whatever hath or shall come to pass in this world, whether it be good, or whether it be bad, proceedeth entirely from the divine will, and is irrevocably fixed and recorded from all eternity in the preserved table; God having secretly predetermined not only the adverse and prosperous future of every person in this world, in the most minute particulars, but also his faith or infidelity, his obedience or disobedience, and consequently his everlasting happiness or misery after death; which fate or predestination it is not possible by any foresight or wisdom to avoid.[30]

RELIGIOUS PRACTICE: —The articles of religious practice are fourfold : Prayer, including Ablution, Alms, Fasting and Pilgrimage.[31]

THE MINISTERS OF RELIGION : —The ministers of religion consists of Scheiks, Yatebs (or Chatebs) Imams, Muezzins, and Kaims.[32]

1st. The Scheiks. These dignitaries are the ordinary preachers of the mosques. The name Scheik, i.e. the elder signifies like our term presbyter or priest, a man advanced in life and superior in virtue. Every Mosque has a scheikh, or preacher of this description.[33]

2nd. The Yatebs (or Chatebs). It is the office of the Yateb to read the “Yutba” or public prayers which are offered up for the reigning sultan in the Mosques every Friday. The Yatebs are also occasionally styled Friday Imams, “Imamot dschumaa,” because the Yutba is only offered offered up on that day.[34]

3rd. The Imams. Imam signifies, properly, the director of prayer, because the whole congregation are expected to direct their eyes by his movements. His office consists in reciting the five usual prayers in the Mosque, at the hours prescribed, save on Friday when that of the Yateb is read. Several Imams are attached to each Mosque (generally two).[35]

4. The Muezzins : — The Muezzins or callers to prayer proclaim the five prayers according to the prescribed form (i), from the minarets of the Mosques.[36]

5. The Kaims : —These officials are like our sextons or beadles only performing the lowest Church services. The eldest of these is called kaim-bashi, (the upper Kaim).[37]

Although these five degrees are recognized as adjuncts to the proper carrying out of the ceremonies of religion, still there is no order of priesthood analogous to that of the Christian Church, each Moslem being a priest for himself.[38]

There are however certain mystic sects of Moslem believers who practice occult rites; these are known as the Dervishes, and they attribute their origin to the Caliphs Abubeker (k) and Ali (m) who took the initial in instituting these fraternities. Though this genealogy may be apocryphal, it is certain that the sufis or mystics of Islam began their rites in the first century of the Hegira, when the Moslem system sustained various modifications by the mixture of Persian, Christian and even Indian ideas. In some respects the Moslem dervish corresponds to the Christian Monk; and the sofi of Islam is clearly analogous to the mystics of Christendom, and of Egyptian mythology. It is estimated that the sects of the dervishes amount to 30. Those which are held in the highest repute, and whose institutions are more or less connected with the civil government, on which they exert considerable influence, are the Nakschbendi, Mewlewi, Begtaschi, Kadri, Chalweti and Rufaai. All these orders have a special costume, of which the headdress is the characteristic feature. Most if not all these orders are divided into seven degrees, each one of which has its own mystic word; these words generally are the mysterious names of attributes of the Deity, as: — 1st. La Ilah illalah (There is no God but God). 2nd. Jallah (Oh God). 3rd. Jah Hu (Oh He). 4th. Ha Hak (Oh, all truthful). 5th. Ja Hajj, (Oh ever living). 6th. Ja Kajum (Oh self-existent). 7th. Ja Kahhar (Oh, all revengeful).[39]

These seven words have a symbolical reference to the seven heavens, sevens hells, seven earths, seven seas, seven colours, seven planets, seven metals and seven tones.[40] The statutes of these order generally provide that each dervish should repeat seven times per day the mystic words of the degrees he has already attained to. The Turkish Sultan Mahmoud the Second, who in 1826 at the head of an already prepared and faithful army of 50,000 men, destroyed the entire body of Janissaries, then numbering some 20,000 men, issued about the same time an imperial decree abolishing the various orders or dervishes[41]; but although strenuous efforts were made to disperse and destroy these sects, still they were but partially successful, and the orders still continue to flourish, and propagate their doctrines and practise their mysterious rites, with the tacit consent, if not the actual approval of the Sublime Porte.

In conclusion it may be of interest to state that the numbers of the adherents of the Moslem religion in 1874 were estimated at from 160 to 200 millions, of which Europe contributed its quota of about 6½ millions.

Those of our readers who desire to pursue this subject further will obtain much valuable information from the following works, Sale’s “Koran,” Irving’s “Life of Mahomet.” The Abbé de Marigny’s “History of the Arabians,” Conde’s “Arabs in Spain,” Gibbon’s “Rise and Fall of the Saracen Empire,” Ockley’s “History of the Saracens,” Morell’s “Turkey past and present,” and Lake’s “Islam.”

WILLIAM QUILLIAM,

Purt-y-Chee, Fairfield, Liverpool.

August 2nd, 1885.

a. The Rabeaa, the Guessane, and a part of the Kodâa [7].

b. The Houmayr, the Beni Kenanet, the Beni Haret, the Beni Kab and the Koudat.[7]

c. Tamimes (sometimes called the Madjoucia),[7]

d. Koreiches,[7]

e. Beni Hanifa,[7]

f. Beni Ismail.[7]

g. Koran, Chap. 1.

h. Koran, Chapters 7 & 38.[42]

i. Very true Moslem is required to pray five times in twenty-four hours. The five orthodox Mussulman prayers are styled—

Salat el fedger…. Prayer at daybreak.

Salat el dohor…. Prayer at 1 o’clock, p.m.

Salat âaseur…. Prayer at 3 o’clock,

Salat el mogrheb…. Prayer at sunset,

Salat el eucha…. Prayer at 8 p.m.

The prayers are earlier or later according to the season.[43]

k. Abubeker was the first Caliph after Mahomet A.D. 632 to 634

m. Ali was 4th Caliph (A.D. 656).

References and Notes:

Source: The Kneph, November 1885, 58-60. Thanks to University of Manchester for providing the journal. The catalogue code is R206125. Thanks to Yahya Birt for editing the article. First published on my Academia page.

- Geaves, R. 2013. Islam in Victorian Britain: The Life and Times of Abdullah Quilliam. 3rd impression. Kube Publishing. p. 60. See also Khan, M. M. 2017. Great Muslims of the West: Makers of Western Islam. Kube Publishing. p. 188.

- It is not known who wrote the diary, however, Geaves argues it may be the mother of Abdullah Quilliam. Geaves, 2013, p. 316n1.

- See Anonymous. 1893. [Untitled]. al-Ustadh. Issue: 30. Pp. 766-768; Abouhawas, A. 2020. An Early Arab View of Liverpool’s Muslims. Also in 1928, Quilliam repeated his conversion story in Cairo, see Cairo Speech – 1928 and for the Arabic transcript, see Anonymous. 1930. Nisf qarn ‘ala al islami fi inkiltra. 7: 200-211.

- Garrard, J. 1882. Quack doctors and their doings: a warning to invalids. Sheffield, UK: James S. Garrard; Manchester and London, UK: John Heywood. p. 19. Geaves, ch. 2; Quilliam, W. H. 1891. Islam in England. The Religious Review of Reviews. 1(3): 159-166.

- Voltaire, the French historian and philosopher, considered the Koran to be “more beautiful than all the Alcorans in the world.” See, Gunny, A. 2017. The Prophet Muhammad in French and English Literature, 1650 to the present. The Islamic Foundation. p. 61.

- Compare to Morrel, J. R. 1854. Turkey, Past and Present. London, UK: G. Routledge & Co. p. 68. “To form a correct judgement of the system and reforms introduced by Mohammed, we shall briefly examine the state of Arabia previous to his advent, as described by an Arab and a Mussulman.”

- Compare to ibid, “Before our lord Mohammed, the Arabs professed divers religions. Some, like the Rabeaa, the Guessane, and a part of of the Kodâa, were Christians; others, like the Houmayr, the Beni Kenanet, Beni Haret, Beni Kaal, and the Koudat, were Jews; others again, like the Tamimes, were Madjoucia, or fire and star worshippers; some including the Koreiches, who kept the keys of the Kaaba, were djahylia – idolaters.

The Beni Hanifa worshipped an immense idol of paste… Finally, the worship of stones were peculiar to the Benu Ismail.” - Compare to ibid, “Among the djahylia every head of a family had protecting deities in his tent or house, which he saluted; the latter in issuing, the former on entering.”

- Compare to ibid, “In the kaaba of Mecca and its precincts were placed, moreover, 360 idols each of whom presided over one of the days of the Arab year.”

- Compare to ibid, pp. 68-69, “The worship of idols has resulted from the grieving of the living for the dead. It is related that Jakout, Jaouk, and Nesrane, sons of Adam, had retired to solitary places, far from their brothers and sisters, in order to consecrate themselves entirely to God. Jakout being dead, Jaouk and Nesrane, by the insinuations of the devil, cast his image in copper, mixed with lead, and placed it in their temple, to have constantly before their eyes the image of their lamented brother. When the Lord called them to himself in their turn, their children did the same thing for them that they had done for their brother, and gradually the following generations confounded in a common worship their ancestors and the true God, and lost at length the traces and tradition of the primitive religion.”

- Compare to ibid, pp. 71-2, “The history of Islam commences with the flight (Arabic, Hegira) of Mohammed, in the year 622 of the Christian era… It has been a matter of dispute among the thinkers of the West, if Mohammed was the deluder of others, or the victim of his own delusions… Without venturing to dissect the mysteries of instinct and inspiration, it will suffice here to say that the seer of Arabia was evidently gifted with a sublime genius, and that he was actuated by divine principles. He regarded himself as an ambassador of heaven, who was sent to his people to lead them to the knowledge of the only true God; and he was convinced that the work in which his doctrine was inscribed, was a book written from all eternity. His adherents maintain that it was imparted to him by the angel Gabriel. In accordance with this conviction, the Prophet required unlimited faith and obedience to the Koran.”

- Compare to ibid, p. 72, “The broad principles and convictions that impressed the mind of the Prophet, and are inscribed on almost every page of his book, fall under the following heads : The doctrine of one only God, of the immortality of the soul, of the duty of man, and to be thankful to his wise and beneficent Creator—not to regard afflictions or external prosperity, if the object is to convert men to God; to make use of reason, which has been lent to us by God, to acquire knowledge, and to honour wisdom and science; and, in general, to provide for well-being and honour in this world and the next.”

- Compare to ibid, p. 72, “In short, if we subtract some exceptional factors from his doctrine, we have a system on most points identical, or analogous to, the simple, sublime, and reasonable theology of Unitarian Christians.”

- Compare with Irving, W. 1874. Life of Mahomet. London, UK: George Bell & Sons. p. 203, “According to the Moslem creed a book was treasured up in the seventh heaven, and had existed there from all eternity, in which were written down all the decrees of God and all events, past, present, or to come. Transcripts from these tablets of the divine will were brought down to the lowest heaven by the angel Gabriel, and by him revealed to Mahomet from time to time, in portions adapted to some event or emergency. Being the direct words of God, they were all spoken in the first person.”

- Compare to ibid, “Besides the Koran or written law, a number of precepts and apologues which casually fell from the lips of Mahomet were collected after his death from eye-witnesses, and transcribed into a book called the Sonna or Oral Law. This is held equally sacred with the Koran by a sect of Mahometans, thence called Sonnites; others reject it as apocryphal; these last are termed Schiites.”

- Compare to Morrel, p. 73, “The third canonical work is the Jdjhay-ummeth, or the explanations and decisions of the most eminent disciples of Mohammed, especially of the four first khalifs.”

- Compare with ibid, “The fourth sacred book is the Kiyas, consisting in a collection of the canonical decisions of the imams, or priests, of the first centuries after Mohammed.”

- Compare with Irving, p. 201, “The religion of Islam, as we observed on the before-mentioned occasion, is divided into two parts : FAITH AND PRACTICE: – and first of Faith. This is distributed under six different heads, or articles, viz: 1st, Faith in God; 2nd, in his angels; 3rd, in his scriptures or Koran; 4th, in his prophets; 5th, in the resurrection and final judgement; 6th, in predestinations. Of these we will now briefly treat in the order we have enumerated them.”

- Compare with ibid, “FAITH IN GOD. —Mahomet inculcated the belief that there is, ever was, and ever will be, one only God, the Creator and ruler of all things; who is single, immutable, omniscient, omnipotent, all merciful, and eternal. This unity of God was specifically and strongly urged, in contradistinction to the Trinity of the Christians. It was in the profession of faith, by raising one finger and exclaiming, “La illaha il Allah!” There is no God but God, to which was added “Mohamed Resoul Allah!” Mahomet is the prophet of God.”

- Compare with ibid, “The beautiful doctrine of angels or ministering spirits, which was one of the most ancient and universal of oriental creeds, is interwoven throughout the Islam system…” and also with Sale, George. 1734. The Koran. London, UK: C. Ackers. Sect IV, p. 71, “…he is reckoned an infidel who denies there are such beings, or hates any of them…”

- Compare with Sale, Sect IV, p. 71, “They believe them to have pure and subtil[sic] bodies, created of fire; that they neither eat nor drink, nor propagate their species; that they have various forms and offices; some adorning GOD in different postures, others singing praises to him, or interceding for mankind. They hold that some of them are employed in writing down the actions of men; others in carrying the throne of GOD and other services.”

- Compare with ibid, pp. 71-72, “The four angels whom they look on as more eminently in GOD’s favour, and often mention on account of the offices assigned them, are Gabriel… Michael… Azräel… Israfil…”

- Compare with ibid, p. 73, “As to the scriptures, the Mohammedans are taught by the Koran that God, in divers ages of the world, gave revelations of his will in writing to several prophets, the whole and every word of which it is absolutely necessary for a good Moslem to believe. The number of these sacred books, were, according to them, 104. Of which ten were given to Adam, fifty to Seth, thirty to Edrîs or Enoch, 10 to Abraham; and the other 4…”

- Compare with Morrel, p. 79, “The Thourat, which was delivered to Sidna Moussa (Moses); the Zabour, to Sidna Daoud (David); Lendjil (the Gospel), to Sidna Aissa (Jesus Christ); the Koran, to Sidna Mohammed.”

- Compare with Sale, Sect IV, p. pp. 73-74, “which last being the seal of the prophets, those revelations are now closed, and no more are to be expected. All these divine books except the four last, they agree to be now entirely lost, and their contents unknown; tho’ the Sabians have several books which they attribute to some of the antediluvian prophets. And of the four, the Pentateuch, Psalms, and Gospels, they say, have undergone so many alterations and corruptions, that tho’ there may possibly be some part of the true word of God therein, yet no credit is to be given to the present copies in the hands of the Jews and Christians.”

- Compare with ibid, p. 75, “The number of prophets which have been from time to time have been sent by God into the world, amounts to no less than 224,000, according to one Mohammedan tradition, or to 124,000, according to another; among whom 313 were apostles, sent with specials commissions to reclaim mankind from infidelity and superstition : and six of them brought new laws and dispensations which successively abrogated the preceding; these were Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus and Mahommed. All the prophets in general the Mohammedans believe to have been free from great sins, and errors of consequence, and professors of one and the same religion, that is Islam, notwithstanding the different laws and institutions which they observed.”

- Compare with Irving, p. 204, “On this awful subject Mahomet blended some of the Christian belief with certain notions current among the Arabian Jews.”

- Compare with Morrel, p. 76, “It is well to observe that the Mussulman’s place of punishment is divided into seven stages or floors, for different classes of delinquents…”

- Compare with ibid, p. 79, “The future place of happiness is called Jannat, a garden, corresponding to the Greek word Paradise…”

- Compare with Sale, Sect IV, p. 103, “This sixth great point of Mohammedans are taught by the Koran to believe is God’s absolute decree and predestination both of good or evil. For the orthodox doctrine is, that whatever hath or shall come to pass in this world, whether it be good, or whether it be bad, proceedeth entirely from the divine will, and is irrevocably fixed and recorded from all eternity in the preserved table; God having secretly predetermined not only the adverse and prosperous future of every person in this world, in the most minute particulars, but also his faith or infidelity, his obedience or disobedience, and consequently his everlasting happiness or misery after death; which fate or predestination it is not possible by any foresight or wisdom to avoid.

- Compare with Irving, p. 211, “RELIGIOUS PRACTICE: —The articles of religious practice are fourfold : Prayer, including ablution, Alms, Fasting and Pilgrimage.”

- Compare with Morrel, p. 139, “The priestly order consists of scheiks, chatebs, imams, muesins, and kaims.”

- Compare with ibid, “The Scheiks. —These dignitaries are the ordinary preachers of the mosques. The name scheik — i.e., the elder—signifies, like our term Πρεσβuτεροι, presbyters, priests, a man advanced in life and superior in virtue… Every mosque has a scheik, or preacher, of this description.

- Compare with ibid, “The Chatebs.—It is the office of the chateb to read the chutba — i.e., public prayers, which are offered up for the reigning sultan, in the mosques, every Friday… The chatebs are also occasionally styled Friday imams, imamot dschumaa, because the chutba is only offered up on that day.”

- Compare with ibid, “The Imams.—Imam signifies, properly, the director of prayer, because the whole congregation are expected to direct their eyes by his movements. His office consists in reciting the five usual prayers in the mosque, at the hours prescribed, save on Friday, when that of the chateb is read. Several imams are attached to each mosque.”

- Compare with ibid, “The muezzins, or callers to prayer, proclaim the five prayers according to the prescribed form, from the minarets of the mosques.”

- Compare with ibid, “The Kaims.—These officials are like our sextons or beadles, only performing the lowest church services. The eldest of these is called kaim-bashi, the upper sexton (or sacristan).”

- It appears that only the last few words were borrowed from ibid, p. 142, “…every Moslem being a priest unto himself.”

- Compare with ibid, p. 138-139, “The dervishes attribute their origin to Abubeker and Ali, who took the initial in instituting these pious fraternities, under the eyes of the Prophet. Though this genealogy may be apocryphal, it is certain that the sufis or mystics of Islam began their heresies in the first century of the Hegira, when the Mohammedan system sustained various modifications by the mixture of Persian, Christian, and even Indian ideas. The dervish of the Mohammedans corresponds to the monk of the Christians; and the sofi of Islam is analogous to the mystics of Christendom. It is estimated that the sects of dervishes amount to thirty. Those which are held in the highest repute, and whose institutions are more or less connected with the civil government, on which they exert considerable influence, are the Nakschbendi, Mewlewi, Begtaschi, Kadri, Chalweti, and Rufaai. All these orders have a special costume, of which the head-dress is the characteristic feature. The statutes of the orders direct that every dervish should repeat, more than once per day, the mysterious names or attributes of God, which constitute, moreover, the usual form of consecration. These words are—1. La Ilah illalah (there is no other God but Allah); 2. Jallah (O God) ! 3. Jah Hu (Oh, He) ! 4. Ha Hak (O, all truthful) ! 5. Ja Hajj (O ever-living) ! 6. Ja Kajum (O self-existent) ! 7. Ja Kahhar (O, all-revengeful) !”

- Compare with ibid, p. 139, “These seven words have a symbolical reference to the seven heavens, seven earths, seven seas, seven colours, seven planets, seven metals, and seven tones.”

- Compare with ibid, p. 47, “Mahmoud, at the head of an already prepared and faithful army of 50,000 men, destroyed the entire body of the Janissaries, of whom at least 20,000 fell. Another imperial decree was also issued at the same time against the dervishes.”

- Copied directly from the notes by Sale, Sect IV, p. 71.

- Compare with Morrel, p. 81, “…and every true Moslem is required to pray iive times in twenty-four hours. The five orthodox Mussulman prayers are styled :—

Salat el fedjer ….. Prayer at daybreak.

Salat el dohor ….. Prayer at 1 o’clock, p.m.

Salat el âaseur ….. Prayer at 3 o’clock.

Salat el mogrheb …. Prayer at sunset.

Salat el eucha ….. Prayer at 8, p.m.The prayers are earlier or later according” to the season.”

Comments are closed.