Please note: the following article includes a word which some may find insulting and hateful. The word has been censored using asterisks.

‘Why did Roman’s build straight roads? So P***s wouldn’t build corner shops.’

So the time-honoured joke goes. Like all racist jokes, it is matched in its bigotry only by its total lack of imagination and humour. And like all tropes that involved South Asian corner shop owners, it evoked a visceral response from me. My cheeks would flush, my spine would bolt upright, a defence reflex that was programmed into me and which, frustratingly, betrayed the shame and embarrassment I was so desperate to mask. The adolescent pressure to appear perennially unmoved and impassive in my youth was made impossible for me by the many racial stereotypes I was forced to navigate as someone of Pakistani heritage growing up in 90s Britain. Chief amongst them was the comical, linguistically deficient “bud-bud-ding-ding-one-ninety-nine” corner shop owner. A stereotype which contains the inherent contradiction of nationalist, racist thinking – framing an industrious and resilient desire to be and contribute with the lazy, parasitic portrayals of immigrants in modern folklore.

With the hindsight of age, this ostensibly innocuous characterisation seems gratuitously cruel. My fathers’ graft and tenacity in running a successful, almost ‘open all hours’ newsagent should never have been a source of shame for me. The idea that our very existence was a punchline wired my already confused, premature thinking, and like racist stereotypes and caricatures that exist the world over, it stuck. It added to the ugly and loathed character which had formed in my head from a plethora of outside voices, forged with every ‘smelly’-curry-based epithet, every depiction of Pakistaniness as unclean, impure, unwholesome, unworthy – which I tried my utmost to distance myself from. It left what felt like a thick and stubborn smell, emanating from my DNA and out through my pours, creating a miasma of undesirability around me. It seemed the national narrative rendering immigrants as impure entities polluting the unspoiled waters of the British Isle had moulded my young mind.

It is easy to trace where the seeds of this wildly misplaced embarrassment regarding the corner shop were sewn. Characters like The Simpson’s Apu which crystallised racial stereotypes in public imagination – which gave them a catchphrase and a funny costume. Which reduced people I loved to one-dimensional characters and which fitted quite neatly into a wider narrative of marginalisation intent on denying people of colour any depth or complexity – or to put it more succinctly – humanity.

While much was done, by the Simpsons and many right-wing commentators, to defend the characterisation of Apu, they were mere distractions from and did little to cover up the fact that, the very nature of these so-called ‘harmless’ racist tropes, jokes and stereotypes is that they are exclusionary in nature. They are made to appeal to a majority audience at the expense of a minority. These ‘knowing’ references are a direct commentary to mainstream audiences, while wilfully avoiding eye contact of the watchful marginal viewers. And while these characters are formed, and jokes are made to appeal to masses, it is very much felt on an individual level to those that it ridicules, mischaracterises and excludes from their narrative – when it is reimagined in the playground, weaponised on the street or hurled from the back of a passing car. And perhaps this is why I don’t view the apparently guileless racial humour of the past through fond, sepia-tinted lenses, because looking back I’m made aware of where my youthful shame and quirks weren’t quite the natural result of adolescence. And that perhaps not everyone had their anxieties exploited, and a currency coined in the trading of jokes aimed at their degradation.

But what I do have defiantly fond memories of, is my time at my dad’s corner shop. And what I do have is a great admiration and respect for is my dad’s sheer hard work, determination and ingeniousness in creating a space that was the opposite of that stereotype. My dad’s newsagent, however unassuming, was a hub for the community. He didn’t exhibit any of the bigoted traits that millionaire media bosses so clearly did, and our newsagent was open seamlessly, 364 days a year, 12 hours a day to everyone in Corbyn’s north London neighbourhood. But this isn’t a story about how our backs were bent in support of a white majority population. Contrary to urban legends, our existence was not supplementary and our sole purpose was not to provide support, counsel, and a shoulder for someone else’s burden. We lived full, whole, tapestried lives, as ground-breaking as this may sound to consumers of mass media. And my dad’s rich, Punjabi accent, which enveloped consonants and wrapped everything he said in a cloak of drama, was a signifier of his lingual prowess, not a sign of its poverty. Unlike what the crude, staccato like parody stood for. His tone and intonation spoke of his ability to carve a life for himself in a foreign land, sometimes in hostile climates.

The pervasive stereotype of the ‘Indian’ corner shop owner as emblematic of all that was undesirable about Pakistani British culture haunted my mum before it did me. The scant few characters of South Asian heritage that illuminated homes during my mum’s youth consisted of rudimentary, prototypical versions of the apparently more progressive depiction Apu. When we look at ‘Punkah Wallah’ of 70’s sitcom It Ain’t Half Hot – an loincloth clad, oft-abused fan bearer – then the argument that current media representation is positive on the basis that it has progressed, alone, feels far more convincing.

My mother and aunt would often trade insults as young girls, growing up not too far from where my dad eventually purchased his own newsagent. They would taunt each other with the prospect of marrying shop owners and becoming mothers to children’s whose first words would be ‘customer!’ Like all good self-fulfilling prophecies both my mum and aunt eventually married proprietors of newsagents. They were incredibly successful and achieving in their own right, while simultaneously helping to man the shop floor, but let us not let facts get in the way of prevailing cultural myths. And though I can’t say ‘customer’ was part of my spoken vocabulary, it certainly entered my psychological lexicon and my earliest memory of people was framed through this economic exchange.

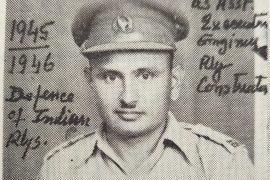

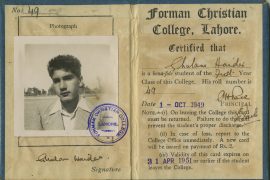

While my mum’s family were undeniably working class, my maternal grandfather came to the UK as a factory worker from a village of the GT road, their British home and accent meant they were deemed an adequate match for my father’s own upper -middle class Lahori background. A bitter-sweet legacy of Empire, it finally being used to oil the hinges of the iron-clad class system of the subcontinent. My parents first meeting in Pakistan was over tea and Penguins, brought back by my grandmother to accommodate her daughter’s now anglicised pallet, in the early 80s. My dad was awed, and they were married shortly after. My father joined my mum to live in the UK and the geographical move westward meant another change in the wind of class, this time for my dad and this time in a decidedly downward motion, but he took to the economic demands of London life like a duck to water. My dad worked in several north London Jewish bakeries, scraping enough money, along with my mum’s civil-servant wage, to purchase his very own newsagent in 1988. By this time, they had two young children who would learn to compete with the growing needs of a business during the tail end of Thatcher’s Britain.

Often my siblings and I were left sleeping in our flat not far from my dad’s shop, while my dad made the pre-dawn run for the morning’s papers and my mum left to open the shop before her own 9-5. My dad’s enterprising nature meant he knew tabloids and broadsheets were essential for his business. While the profit he made on the often racist-filled pages was negligible, they were absolutely necessary to draw in the quotidian grind of customers. Something the charming Trevor Kavanagh was no doubt aware of when he made his infamous comments in vindication of The Sun’s increasingly Islamophobic editorial line. Of course, Muslim newsagents like my dad whose precarious social and economic standing meant they could not afford to be principled about what kind of news content they were selling. Kavanagh’s shrewd comments, essentially holding a class of newsagents hostage, are just another example of the experience of people of colour being erased, written over and mocked. The Sun is comfortable in its position of falsely speaking on behalf of Muslims who are clearly so accustomed to becoming political fodder that it appears we have reached a stage where we feel our vilification in public discourse is both normal and unquestionable. Much like how my mum and aunt’s retorts regarding the stereotype of the South Asian corner shop contained in them a resignation as well as an attempt to disavow that experience, my dad had equally distanced himself from the racist caricatures carved out on the sheets of the papers that sat menacingly on his front desk.

There were ruptures between this national media discourse of racism and our own relatively harmonious existence at the time. My mum was heavily pregnant, sitting behind the counter on her weekend off from her full-time job, when she was subject to a tirade of abuse from a neighbouring homeowner for ‘only being good for having babies’. My mum who taught English at a women’s prison, who painted, sculpted, wrote and went on to complete a Literature degree with four young children. Or the local skinheads who stood threateningly outside the Doc Martens shop on the local high street who did nothing to hide their ire at our existence.

But thankfully these memories are few and far between. They make rare punctures through the fond memories I have of the appeasing taste of a lukewarm strawberry Yazoo straight off the cash and carry floor at the end of a gruelling wait, the sweet smell of cardboard which flooded the shop and the lost taste of a Snickers bar from the 90s. Of fish and chips and a blanket at the back of my mum’s car, in the flashing lights of London traffic on late evenings home from the shop. Of playing hopscotch in the punishing London heat with our amazing Chinese neighbours who lived to the right of our shop and whose existence was far less sheltered than our own – they would often lead us hand in hand, dodging young men high on heroine, to the local Woolworths to covertly feed our own sugar and pink plastic addiction. Or our friends from the Irish traveller community who lived behind the shop and with whom we once discovered a glistening 50p piece that had fallen to a basement flat. On this occasion, we negotiated a 50p chewing gum loan off my dad, that we sat chewing desperately to form a sticky mass which we affixed to the bottom of a long stick in a vain attempt to fish out our fortune. Suffice to say this was one of my dad’s less successful business ventures and he did not receive a return on this questionable investment. Of my first insight into middle-class existence, in the form of our wealthy neighbours across the street who owned an actual piano and where we had our first and last accidental taste of bacon. And the smell of cat vomit that plagued their house over Christmas as their cat had a sickly addiction to pine needles.

My dad did work diligently on making his shop a success, he was responsive to his customers’ needs, and the commercial architecture of the shop – with bright water guns and other inviting plastic toys suspended across the top of his counter like low hanging fruit – meant the difference between pennies and pounds in his modest enterprise. He was equally adaptive in the face of the legislative crisis of the Sunday Trading Act of 1994 which saw his profits collapse, as supermarkets took the lions share of his most profitable working day. In the face of supermarket hegemony, and against the trend of corporate dominance, my dad extended his working day to 15 hours to make up for this shortfall. As ever, my parents artfully drew on themselves to avert crisis and remain afloat often against all odds and in the face of adversity.

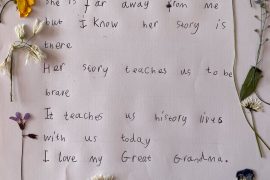

My dad eventually went on to sell his shop, and like the resourceful man he’s always been, undertook a string of other ventures. Always working late into the night and always intent on maximising his opportunities. He, and my family, were never defined by our time at our newsagents and we continue to exist outside of it. But standing here as I am today, two generations on, I at least want to reclaim the reductive stereotype of the ‘Indian’ corner shop, and its subsequent reinterpretation as noble, ingratiating support character in someone else’s story. And I want to replace it with my dad and his resolve in creating a better life for my siblings and I. I’m pleased to say my spine now unfurls in pride over the memories of being the daughter of a remarkable corner shop owner.

Mariya bint Rehan

Comments are closed.