On the 18th February 1932, a 42-seater Imperial Airways aeroplane took off from Croydon, its destination: Paris. Onboard was Gladys Milton Palmer, the former British socialite, heiress and only daughter of the late biscuit manufacturer and Conservative MP for Salisbury, Sir Walter Palmer. As the plane flew 4000 feet over the English Channel, Gladys, wrapped in a dark fur coat, got up from her seat and made her way to the front of the cabin. In her hand was a small gold book the size of a postage stamp – a minute copy of the Quran. [1]

Khaled Bertram Sheldrake, president of the Western Islamic Association was also on the flight. Both stood facing their fellow passengers before Sheldrake proceeded to explain the fundamental tenets of Islam. Gladys then began to repeat the Shahada (the Muslim declaration of faith), first in Arabic and then in English: “There is no god but God, and Mohamed is His Prophet”.[2] Once a “Society Girl”, Gladys was now a Muslim.[3]

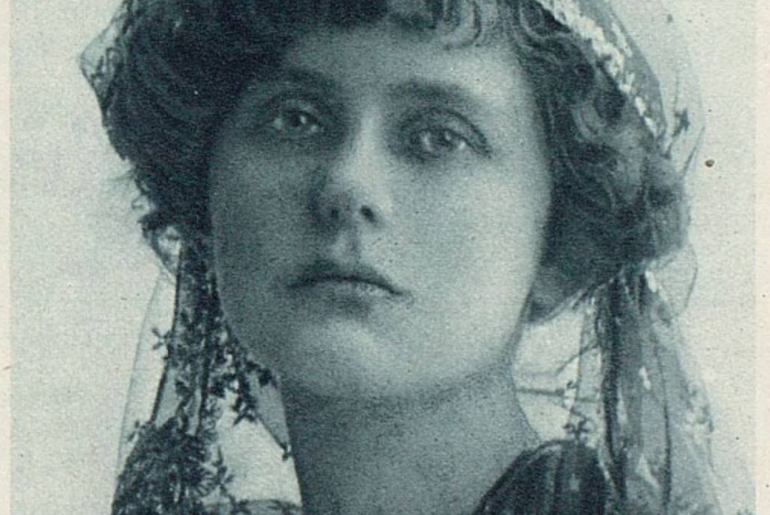

Born in 1884 she grew up between the Frognal Estate in Sunninghill, near Ascot and 50 Grosvenor Square in Mayfair. Described by the society magazine Tatler as “tall and very beautiful”, she was a well-known figure in London and Paris society, rubbing shoulders with celebrities and the elite.[4] At the age of twenty, she married Bertram W. D. Brooke, second son of the Rajah of Sarawak, in a ceremony attended by members of high society and the aristocracy, including Princess Christian – the third daughter of Queen Victoria.[5] Through her marriage, Gladys became a member of the ruling ‘White Rajahs’ – a dynastic monarchy of the British Brooke family who ruled the Raj of Sarawak, an annexed domain on the north-west coast of Borneo – and was given the title Her Highness the Dayang Muda of Sarawak.

Gladys appears to have been a relatively eccentric character, described as having “bohemian and artistic tastes.” [6] In 1922 she formed a short-lived film production company that produced one film the same year before it went into insolvency. In the late 1920s, while living in Paris, she authored (although it was in fact ghost written) a memoir entitled ‘Relations and Complications’ which included revelations on the literary and artistic circles she was involved in. And at one point she even ran an antique shop in the famous Burlington Arcade off Piccadilly “as a hobby.”[7]

Her foray into finding a religion she could accept saw her renounce Protestantism; moved on to Christian Science; then Catholicism, before adopting Islam, while her husband remained Protestant throughout. She first became interested in Islam through her own personal research into a tunic purported to have belonged to the Prophet Mohammad. Valued at £500,000 in 1932 she became the guardian of the relic.[8] She then spent several months prior to her conversion intently studying the Quran. “I particularly wanted to become a Moslem in an aeroplane” she is quoted as saying to a journalist who was on the flight with her, “so that I might be as far from earth and as near to heaven as possible.”[9] She anticipated alienation from her family and society but probably was not expecting criticism from her fellow Muslims, some of whom saw her conversion as a publicity stunt. Lord Headley, President of the British Muslim Society, for instance, commented: “When a woman of such importance selects an aeroplane for so serious a ceremony it is, to say the least, unfortunate…I do not want to be unkind, but I feel that her action is liable to be misconstrued as a desire for notoriety and even as a somewhat freakish departure from good taste.”[10]

Despite the disapproval, Gladys proved resilient and was still very much moving within the upper circles of society despite her conversion – although she did manage to stir up some controversy. A month after becoming a Muslim she was invited as a guest at the Rhyl May Day festivities where she had the honour of crowning the 43rd May Queen.[11] At the ceremony, she planned to present the May Queen with a copy of the Qur’an – a proposal that drew a number of disapproving comments and reservations. However, Gladys stood her ground and was said to have found the concern “very amusing.” “I am a Moslem now” she is quoted as saying, “It has required great courage to change my religious faith. All the same, I shall give a copy of the Koran to the May Queen and shall autograph it as a memento of the occasion.”[12]

She remained a Muslim until her death in June 1952 and was buried with full Islamic rituals. But, ever the character, she was reported to have left £100 for a funeral champagne lunch, followed by a show at a theatre for her mourners.[13] The Liverpool Echo recounted her will as stating: “ It would be my wish that you will all dress in white or gay colours in order that you should not depress me by looking like a lot of crows, for everyone is sent into this world with a return ticket and must someday leave it and this I shall then have done and so au revoir and God bless you all.”[14]

Written by: Fatimah Amer

Image credits/descriptions:

Gladys 1: The Tatler, 10 April 1912

Gladys 2: Photograph from her memoir ‘Relations and Complications. Being a Recollection of H.H. The Dayang Muda of Sarawak’, published in 1929.

Gladys 3: Gladys Palmer with Khaled Sheldrake on the aeroplane on the day of her conversion, 18th February 1932.

Gladys 4: The Sketch, 7th August 1918.

[1] Daily Mirror, Friday 19 February 1932

[2] Ibid.

[3] Daily Herald, Saturday 3 September 1932

[4] The Scotsman, 8 July 1929.

[5] Gentlewoman, Saturday 9 July 1904.

[6] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Saturday 25 May 1929.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Western Mail, Thursday 24 March 1932.

[9] Daily Mirror, Friday 19 February 1932.

[10] Daily Mirror, Saturday 20 February 1932

[11] The Scotsman, Wednesday 16 March 1932.

[12] Dundee Evening Telegraph, Wednesday 04 May 1932.

[13] Daily Herald, Tuesday 5 October 1954.

[14] Liverpool Echo, Saturday 15th May 1954.

Comments are closed.