Abdullah Quilliam (1856‒1932) has always presented a puzzle to researchers who attempt to dig more deeply into his life and the institutions he was involved with. They quickly come to realise that he was a master of self-promotion, both of himself and the causes and institutions he championed. He not only did this as the co-founder and leader of Britain’s first mosque community but also in his professional and civic roles too, which were numerous. As a journalist and editor of his own periodicals and the author of several books, Quilliam left us with a huge literary legacy, which itself has not yet been fully analysed, with many avenues of inquiry still left uncharted. As research into this significant historical corpus has progressed, it has become increasingly apparent that it has to be analysed carefully and cross-referenced with independent sources (where available) as instances of exaggeration and even deception have been identified. Therefore, even if it remains an invaluable, even unmatched resource for Islam in Britain at the turn of the twentieth century, this corpus can no longer be taken at face value in every instance. This means that a phenomenological approach, which emphasises the primacy of individual subjectivity and lived experience, or, even at a more popular level, a hagiographical attitude, has to give way to a more critical historical approach to the sources if a serious attempt to resolve various mysteries and contradictions is to be made. Although it is outside the scope of this review to delve into it, the two approaches can be combined to marry the best aspects of each, i.e. sympathy for the human subject with the rigour of contextualised source criticism, to form critical phenomenology.[1]

Abdullah Quilliam (1856‒1932) has always presented a puzzle to researchers who attempt to dig more deeply into his life and the institutions he was involved with. They quickly come to realise that he was a master of self-promotion, both of himself and the causes and institutions he championed. He not only did this as the co-founder and leader of Britain’s first mosque community but also in his professional and civic roles too, which were numerous. As a journalist and editor of his own periodicals and the author of several books, Quilliam left us with a huge literary legacy, which itself has not yet been fully analysed, with many avenues of inquiry still left uncharted. As research into this significant historical corpus has progressed, it has become increasingly apparent that it has to be analysed carefully and cross-referenced with independent sources (where available) as instances of exaggeration and even deception have been identified. Therefore, even if it remains an invaluable, even unmatched resource for Islam in Britain at the turn of the twentieth century, this corpus can no longer be taken at face value in every instance. This means that a phenomenological approach, which emphasises the primacy of individual subjectivity and lived experience, or, even at a more popular level, a hagiographical attitude, has to give way to a more critical historical approach to the sources if a serious attempt to resolve various mysteries and contradictions is to be made. Although it is outside the scope of this review to delve into it, the two approaches can be combined to marry the best aspects of each, i.e. sympathy for the human subject with the rigour of contextualised source criticism, to form critical phenomenology.[1]

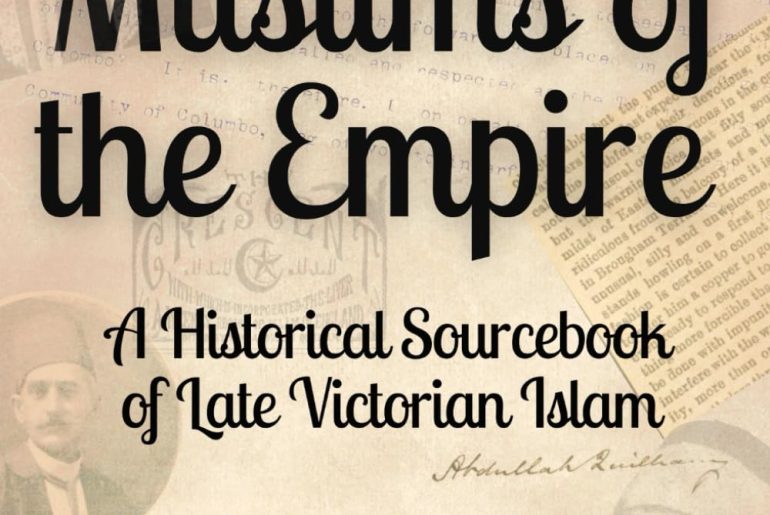

This week has seen a milestone in Quilliam Studies, a subfield within the larger field of British Muslim Studies, with the publication of a sourcebook of over five hundred primary sources, many hitherto unpublished, on the first mosque community in Britain. In its first stages, Quilliam Studies focused upon Abdullah Quilliam’s publications, those he wrote or had editorial control over. Building on the work of others, Riordan Macnamara’s Muslims of the Empire: A Historical Sourcebook of Late Victorian Islam (independently published through Amazon, 2025, 557pp, paperback, £23.95; Kindle, £9.00, ISBN 979-8283773582) represents a huge leap forward in collating disparate sources together from almost entirely outside of Quilliam’s publications, with a considerable number translated from French (the Ottoman diplomatic language), Ottoman Turkish, Arabic and Urdu. These disparate sources include archival diplomatic correspondence, police and intelligence reports, travelogues, newspaper articles, missionary polemics, journals, and devotional literature, as well as selections from Quilliam’s periodicals. Macnamara is a senior lecturer at the University of Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines in France.

The Sourcebook comprises thirteen chapters with synoptic introductions to contextualise the material, which are substantial in their own right and contain new insights even for experts in Quilliam Studies. These are (i) Quilliam’s conversion, (ii) the religious and social activities of the Liverpool Muslim Institute (LMI), (iii) assessments of Quilliam’s character and agenda, (iv) converts and conversion at the LMI, (v) the LMI’s connections with India, Europe and America, (vi) the religious discourse of the LMI, (vii) liturgy and religious practice at the LMI, (viii) eyewitness accounts of the LMI, (ix) local verbal and physical attacks on the LMI, (x) campaigns and activism by the LMI and others, (xi) receptions of the LMI in Europe, the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, (xii) unfinished projects of the LMI and its closure, and (xiii) miscellaneous items.

The selection is wide-ranging and excellent, and it assumes that the serious researcher will understand the Sourcebook to be an essential supplement to the online digitised archives at the Abdullah Quilliam Society (AQS), which includes Quilliam’s major periodicals and books. They are meant to be read in tandem.

If we imagine Quilliam as a defendant in the court of history, then the AQS digital corpus would be seen as the documentary evidence for the defence, while the Sourcebook constitutes the casework file for the prosecution. While some defenders appear in the collection, including Quilliam himself, it is the doubters and the critics who predominate. Overall, the period of the Institute’s flourishing and international impact in the 1890s was also its most tumultuous, given the challenges it faced to its reputation and standing. These ranged from local street ruffians, who in one instance were linked to the Orangemen, to antagonistic Christian missionaries, Indian Muslim activists, Muslim sailors, Ottoman diplomats and travellers, Arab intellectuals, and disenchanted converts who were erstwhile members of the LMI.

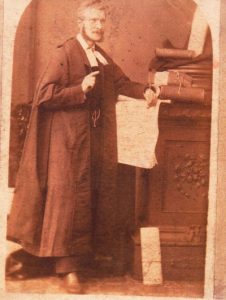

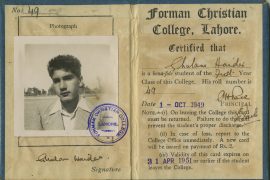

Quilliam as a young lawyer, yet without accounting for all the surviving evidence about his life, how could the court of history judge him fairly?

Since the origins of Quilliam Studies, which date back to the 1970s with Akram Khan-Cheema’s master’s thesis on the LMI (an educationist who also, among other things, helped to develop Liverpool’s Al-Rahma Mosque), community and academic interest in this first mosque community have gone hand-in-hand. At times, they have worked harmoniously, and at others, they have been in tension. Those who take Quilliam’s account at face value or even consider anything other than hagiography to be an affront to the Sheikh’s memory will find the Sourcebook challenging to read. Yet a precondition for a more serious historiography is to consider carefully all the primary sources and compare them critically to attempt an even-handed interpretation. Macnamara reiterates an essential point in the Sourcebook that Quilliam had close relations with some of the local press and regularly fed copy to friendly Liverpool editors that was uncritically regurgitated. Thus, these outlets cannot be regarded as wholly independent sources but should be treated as an extension of Quilliam’s public relations efforts on behalf of the LMI. Critics at the time pointed out repeatedly that Quilliam would exaggerate or make things up for the press, which was a cause of great frustration on their part. As the Ottoman journalist Yusuf Samih Asmay put it, Quilliam, as an English lawyer and journalist, had “the ability and power to make a grain as small as a speck appear as big as a ladle” (Asmay, Islam in Victorian Liverpool, p. 74).

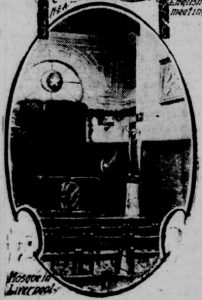

The two aspects of the mosque at Brougham Terrace, left: chairs set in rows for the Sunday Divine Services, while, right, the mihrab facing “Meccawards”, as the community described it, can be seen. The stage and the pews were at the end opposite to the qibla end.

The Christian and Muslim critics agreed that the Liverpool Muslim Institute had developed a distinctive Anglo-Islamic form of worship, presenting basic Islamic doctrine in the form of a Protestant evensong Sunday service. Additionally, the congregational Islamic prayers were eccentric in form, although they incorporated more Hanafi features over the LMI’s lifetime, while retaining Anglophone elements. For context, Macnamara includes other contemporaneous forms of Anglo-Islamic syncretism, such as Abdul Hamid Snow’s Church of Islam in India.

The Muslim critics also focused on the administration of the mosque, with accusations of financial impropriety. The crisis point was in 1895–6 with the fallout from a visit from the Crown Prince of Afghanistan to the LMI and his gift of £2500. Indian, Turkish and Arab activists in England and Egypt, the Ottoman trade consul for Liverpool, and some of the former LMI convert members made a concerted effort to convince the Ottoman authorities and also Muslim public opinion that Quilliam was corrupt and unfit for leadership.

However, Quilliam retained the favour of the Ottoman court, but the criticisms did ensure that the support in 1898 for his planned purpose-built mosque and mausoleum was not forthcoming. The Sourcebook provides a front-row seat by providing all the relevant documentation on this crisis. The 1890s are best represented in the Sourcebook, but the second decade of the LMI’s existence is much less so, e.g. Quilliam’s mission to Rumelia in 1905 on behalf of Abdulhamid II to investigate irredentism there goes unmentioned.

While the synoptic introductions are highly innovative and insightful, as space is limited, I will only comment on some of the interpretations Macnamara offers. Concerning Quilliam’s public identification as a Muslim, Macnamara dates this to 1889 because he emphasises public descriptions of Quilliam as Muslim in the local press, but this makes little sense to me, given that his public mission began in 1887 by working through the Temperance movement for about 18 months, during which a dozen or so people converted to Islam.

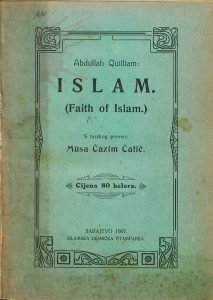

Macnamara astutely remarks on the narrative similarities between the conversion stories of the early converts and the first Companions of the Prophet; I would point out that one of the key texts for the pre-conversion Quilliam was Washington Irving’s 1850 Life of Mahomet, and any further investigation would fruitfully start there. Macnamara correctly recognises Quilliam’s debt not only to British Orientalism but to Indian Islamic modernism of the Aligarh variety, but the question remains as to what his distinctive reformulation of these were in dialogue with the other intellectual influences upon him, say in comparative religion and philology or the sciences (geology or Darwinian biology), not to mention his later interests after Liverpool in Sufism and Abbasid and Ottoman poetry and literature. The favourable reception among reformist ulama of Quilliam’s The Faith of Islam in Türkiye, Iran, Bosnia and Egypt shows they found his civilizational argument for Islam to be sufficiently novel to merit endorsement through translation.

The famous poet and Islamic reformer Musa Ćazim Ćatić’s translation of Abdullah Quilliam’s Faith of Islam in Bosnian. Published in Sarajevo in 1907, it demonstrates the reach and appeal of Quilliam’s first major work on Islam, which went through three English editions. It was also translated into Arabic (twice), Ottoman Turkish, Persian and partially into French.

Finally, on the vexatious question as to why Quilliam abandoned the LMI in 1908, which promptly dissolved, not all the relevant external sources have been included in the Sourcebook. Quilliam’s own cover story that he had been called to Istanbul at short notice on urgent official court business is not corroborated by the Ottoman archive, so it can be dismissed. Macnamara provides useful new context here that Quilliam’s associations with radical Indian pan-Islamists like Riazuddin and Barkatullah could explain his sudden departure, alongside his debarment as a lawyer in 1909. But while this may explain Quilliam’s official barring from travel to British India even into the 1920s, for me, more interpretive work is needed to put forward a more complete hypothesis as to why Quilliam left Liverpool for Istanbul (only for three months, according a Liverpool Echo article), abandoned the LMI to its fate, and changed his identity. Macnamara helpfully notes that in the very same period when British intelligence confirmed that Riazuddin was a Russian agent in 1907, he also invited Quilliam to do a speaking tour of the Punjab, which he agreed to do the following year (a plan that never came to fruition for obvious reasons). Quilliam’s connection with Riazuddin cannot have escaped the attention of British intelligence, and he had already popped up on the radar of the national authorities, which, after gathering unfavourable police reports, recommended against him being granted the Royal Exequatur for his appointment as the Ottoman Honorary Consul General in Douglas (Isle of Man). I will return to this bigger political picture at the end after discussing other factors far closer to home that played into Quilliam’s departure.

Part of the reason for his departure may have been that Quilliam could no longer afford to subsidise the LMI (to the tune of two-thirds of its income if the Crescent is to be believed here) once he could not practise as a lawyer. Controversially, the mosque premises in Brougham Terrace, bought with Muslim donations, were registered in his name rather than in a trust administered by the mosque community. It was sold off in short order by his son, Billal (articulated as a lawyer by his father), presumably on Quilliam’s instructions.

A crucial detail is that Quilliam was accompanied to Istanbul by Martha May Thompson, the woman whose divorce petition he was found guilty of falsifying evidence for (his oldest son, Robert Ahmed, the Ottoman vice trade consul for Liverpool, also travelled with them). Given that Quilliam had supported three wives and families (Geaves, Islam in Victorian Britain; Hamid and Birt, Our Fatima of Liverpool) amid allegations of womanising (Asmay, Islam in Victorian Liverpool, p. 99), it is reasonable to wonder if Quilliam and Thompson were romantically involved with each other. Certainly, his poetry in 1907–8 points suggestively to a personal struggle with a romantic infatuation (Geaves and Birt (eds) The Collected Poems of Abdullah Quilliam, pp. 115–29). And why would Thompson, an impoverished tobacconist from Liverpool, have made the long and expensive trip to Istanbul with Quilliam? On top of that, Thompson was subsequently engaged in marriage in Istanbul to Ahmet, the son of Hannah Robinson, a convert whose marriage to Dr. Gholab Shah Quilliam had been officiated at the LMI in 1891 (Gareth Winrow, Whispers Across Continents, pp. 169–73).

Therefore, the possibility remains that the scandal Quilliam was fleeing was not just legal but highly personal, in which he falsified court evidence for love, destroying his career and alienating his two surviving wives, Hannah and Mary, and their respective families in the process. Furthermore, falsifying evidence in divorce cases was commonplace as the restrictiveness of English law made the grant of dissolutions exceedingly difficult – it was seen as a stratagem to get women out of difficult and abusive marriages (in fact, Quilliam’s allies and friends defended his misconduct in Thompson’s divorce case as a selfless act of gallantry). We will likely never find the definitive evidence to prove it beyond reasonable doubt, but if Quilliam was a man whose card was now marked for his association with Riazuddin, then one could speculate that the authorities took the opportunity presented by his misconduct in the Thompson divorce case to strip him of his status as a solicitor. Despite his practised ingenuity at riding over previous crises, it may well have been a perfect storm of high imperial politics and professional compromise for romantic love that brought Quilliam down in 1908. And God knows best the truth of matters.

In summary, the Sourcebook represents a practical realisation of Jürgen Nielsen’s dictum many years ago that, as the early history of Islam in Britain was written in the major Islamic languages and represented a distributed archive, it would require serious work to bring it back together to form a more complete picture. It is not an exaggeration to say that this work has now begun in earnest in Quilliam Studies, and, in this regard, this subfield is a leader within British Muslim Studies. As such, the Sourcebook should be an integral part of undergraduate and master’s modules on British Islam. It will be keenly read outside of academe within British Muslim communities, given their emotional investment in the history of this pioneering community, which predates the great Commonwealth migrations by six decades, pointing to deeper roots in Britain than is commonly appreciated. More broadly, the Sourcebook is a crucial contribution to the religious history of the British Isles in general, given the rise of Islam in the last 150 years from marginality to the country’s second-largest faith community.

Author – Yahya Birt

Yahya Birt is a community historian who lives in Bradford.

Riordan Macnamara is a Senior Lecturer at UVSQ – University Paris-Saclay

References

[1] Philosophical phenomenology and a critical historical method have been combined to form a novel approach – critical phenomenology, i.e. “One kind of critical phenomenology undertakes a third-person critique of societal structures, inspired by critical theory or poststructuralism, and combines it with a phenomenological analysis of the first-person experience of what it feels like to live under such conditions. Another approach to critical phenomenology finds the critical impulse in first-person experience itself. Here, the excessive limit experiences of breakdowns, perplexing particulars, and interruptions endured by people in their ordinary lives are explored phenomenologically as the loci of an indigenous critique of the prevailing societal orders and of the potentiality for things becoming otherwise.” Rasmus Dyring, “Critical Phenomenology.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Accessed 20 May 2025. https://oxfordre.com/anthropology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.001.0001/acrefore-9780190854584-e-461.

Comments are closed.