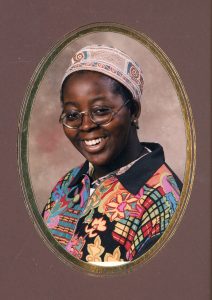

Wasilat Daniju is a part-time therapist and freelance photographer. She was born in 1979, in London, where she still lives and works. Her passion for both art and working with people found its roots quite early into her life.

Wasilat’s first language is English and is also proficient in Yoruba, a language spoken at home which she picked up during her childhood. ‘When my mum’s mum came to visit us, and she barely spoke any English, and I think that was when I really started learning it and speaking it so I’d speak it with her.’

Wasilat started with primary school in Luxembourg, where her father briefly worked. Almost a year later, she moved back to England, where she lived between Tonbridge and London. She moved schools from Tonbridge to Brixton and back over the course of a few years as she completed her schooling. In year 10, she found herself volunteering for VSU voluntary service, where she worked with children and young adults from low socio-economic backgrounds, as well as the elderly. She was also a member of the Literature, Arts and Mime society at school.

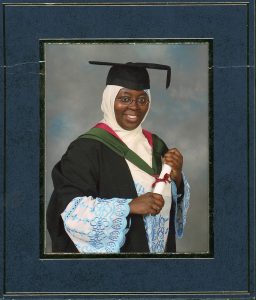

With multiple university degrees to her name, Wasilat identifies her pleasant and rewarding academic and social experience in university as what kept her going back. She graduated with a BSc in Economics from Hull, a degree complete with a year abroad at the University of Hasselt in Belgium with the Erasmus programme. It is here, where she would then get her MBA, as well. Soon enough after a few years, Wasilat was once again returning to higher education and enrolled herself in the University of Sheffield to get a Master of Medical Science in Clinical Communication Studies. She qualified as a Speech and Language Therapist. She later completed a post-graduate diploma in Person-Centred therapy at Strathclyde University. To Wasilat, university life had felt like a step into freedom, and she reminisced about all the ways she grew as a person and found herself while living away from home and meeting new people. ‘I definitely gained a lot of confidence from living away in uni, especially with my Erasmus when I was away and again lived with and studied with students from all over Europe.’ She was active with many extracurricular activities throughout her time as a student. In Sheffield, being a member of the film society, she worked as an usher in their on-campus cinema and then took up a role as a fire officer.

Wasilat, was also involved in the International Society for Economics Students (AISEC), something she had started back in her days at Belgium. She fondly recalls Sheffield being the first place where she made Muslim friends she felt connected with. ‘I had Muslim friends from my first degree, but it felt like this real shift in terms of having Muslim friends who practised a particular way but weren’t insistent that you needed to be that way.’ Academically, compared to economics, studying for her counselling and speech therapy courses, had been a lot more demanding. It held a sense of responsibility that came with working with other people.

As a child, visiting Nigeria had been a wholesome experience. Even though Wasilat does not fully recall, her mother tells her how she had wanted to stay there. On her most recent visit, around 6 years ago, she felt instantly embraced one moment but foreign the next. ‘So even though I speak the language and know my family to a degree, I’m still this Londoner. It’s a weird feeling that I don’t fully belong there in the same way that I don’t belong here.’

Discrimination based on race, culture, and faith permeates societies worldwide and has remained an issue that transcends time. Growing up in London in the eighties and nineties, Wasilat was aware of it to some degree. What she experienced then were mainly microaggressions which at the time struck her mainly as odd. Mentioning her father’s role as an imam of the Brixton mosque cost her a potential seat at a private school. She was ten at the time and did not understand why her mother later berated her for having divulged that bit of truth. ‘It never occurred to me that was a thing that people would have a problem with. Someone being Muslim or being actively Muslim.’ In another instance, she remembers when prostrating on the ground as she demonstrated how Muslims pray, a teacher remarked how that must’ve been the reason why her nose is flat. She did not dwell upon it much but thinking back it was not befitting a teacher to have made a racist remark of that sort, towards one of their students. There were always talks of Black children having to be twice as good to get half as much, a fundamental of living many Black people have had to adopt in a society that perceives one based upon their apparent race, ethnicity or faith.

She laments over the deteriorating condition of the society, one that is plagued by racist attitudes. ‘Unfortunately, if anything I think it’s got worse over recent years. We’re not quite back at slavery levels yet, but it feels like it’s got atrociously bad.’ The institutionalisation of racism leaves violent and overt acts of racism unchecked; as a result, devaluing and risking the lives of particular religions and ethnicities.

In places like Brixton, Camberwell and Soho, she’s been told to ‘go home’ and ‘get out of [their] country’, often by random white men. She was working in Portsmouth when the events of 9/11 unfolded, marking a shift in how Muslims are perceived and treated globally. ‘I just remember these kids running around ‘Osama! What’s in your rucksack? You got a bomb in your rucksack?’. In a more malicious incident, she was followed by three men down a shopping street, who hurled racist insults at her all the while. While fortunately, no physical harm occurred thanks to an onlooker who reported her pursuers to the police in time, Wasilat recalls it being that one time where she genuinely feared that something might happen. In a recent encounter, she was spat on by a woman passing her on the street. Upon confrontation, the woman’s simple reply had been ‘oh you people have attacked me, oh you people, your family, you people’.

When asked about marriage, Wasilat, who is unmarried, expresses her uncertainty regarding ever marrying outside of her religion. ‘Maybe later down the line I’ll bring home some Christian guy and get disowned’ she jokes. Muslim women marrying outside of religion was not something she had considered until of late, and it remains a new idea she has never seriously contemplated. She never questioned the rule that only men were allowed to marry women who weren’t Muslim in Islam. In contrast, she sees herself marrying someone who is not Nigerian or Black but acknowledges that the two parties would have to go many extra miles to completely understand each other’s families, communities and so on.

When it comes to dating and marriage, Wasilat says, ‘it was supposed to be this thing that I’m well versed in but hasn’t happened yet.’ In adherence to their faith, dating is not a common practice among Muslims, who instead prefer to meet someone with marriage intention. However, even marriage requires meeting someone. Wasilat, and many other Muslim women, find themselves on the short end of the stick when it comes to that. Free mixing of genders is frowned upon in many Muslim societies, and Muslim girls, in particular, tend to grow up with several constraints; ‘don’t do this, cover yourself, stay away from boys’. Going from these restrictions to marriage can be a big leap, for which many are unable to find their footing. Furthermore, Wasilat recognises the differences between what men and women expect from relationships. From her experience of dating and marriage websites, Wasilat, who is almost forty years old notices how men her age often seek out younger brides, as young as half their ages. ‘I don’t know, maybe they want to have their second set of children, but there’s something of considering women their own age an oddity.’ There’s also a preference for lighter-skinned Black women, while some go as far as to specify their inclinations towards white, Asian, and European women, followed by a very specific ‘no Black’ in there.

Her first job ever had been that of a babysitter. She’d been fourteen and looked after her Spanish teacher’s child. It had not been without its blips, and despite a few things going wrong, the teacher kept calling her back. Wasilat qualified as a counsellor in 2014. Her inclination to work with people was reflected in her career choices. She worked with young refugees and asylum seekers, first indirectly as a Volunteer Coordinator and later more directly when she established a new therapy service within the organisation. After leaving this role, she briefly pursued photography full-time as a freelancer. However, work was difficult to come by, and she eventually was offered the chance to work at another, smaller migrant organisation, once again establishing and running a new therapy service.

Photography still remains significant to Wasilat who says, ‘it’s something that I’ve done, it’s something that I’ve always enjoyed.’ What motivated her to keep going and pursue it as something more than just a hobby was when her work piqued others’ interest and admiration. When asked if her faith played a role in choosing career paths, Wasilat denies an explicit relation to her faith and choices. However, she does recognise how faith embedded into her the principles of supporting others and working for the betterment of society. Islam, after all, definitely plays a role in how she perceives the world and navigates it. She has never limited herself to helping just Muslims but has wanted to reach out, both as a counsellor and a photographer, to women and people of colour in general. Furthermore, with regards to counselling, like many other counsellors, she believes that helping people heal would bring her healing as well.

Wasilat has been fortunate to be working at The South London Refugee Association, which has been very accommodating to her religious duties, such as, prayer and fasting the month of Ramadan. ‘I feel it would be a bit difficult for organisations if they allow people cigarette breaks, not to allow people to pray.’ Prayer rooms in London are not always dedicated spaces of worship, and people often get creative with making use of empty spaces like storage rooms or filing cabinet rooms. While it is difficult to get the month of Ramadan off, work schedules can be flexible, allowing her to skip lunch and instead go home earlier. She has also found her colleagues more understanding of her slightly low energy levels when fasting. It is generally understood that people must be a little bit more compassionate at this time.

As a child, she was aware of being Muslim, and that she was involved in certain practices and activities like going to the mosque, madrassa and Quran classes because she was Muslim. Wasilat feels like religion became something of her own in her teens. As she grew older, Islam remains something that evolves with her, belongs to her and feels like it’s something personal she has control over ‘Sort of like, changing waves of my faith and how important it is to me and me being able to decide on it.’

Wasilat, also remembers going to the Regent’s Park mosque where they would host the Eid prayer and a celebration. Everyone would dress up and look forward to all the food and festivities. Later, when their local association built its own mosque, it became the place for Eid prayer; however, ‘it felt there became this element of work as well. So my mum would sell things at the mosque so we would stand with her. I remember being like ‘this doesn’t feel like Eid.’ Recently she finds herself more actively engaging in the Inclusive Mosque Initiative trying to bring an element of celebration and fun to Eid. ‘Henna and dancing, eating and it being quite chilled.’

Ramadan can be challenging when calling for an organised schedule, especially when the days are longer and night shorter. ‘Fitting in the different prayers, fitting in the time to eat, fitting in sleep, and when I’m working, I must be really careful about my energy levels.’

To Wasilat, faith is something she constantly evaluates and works on. Sometimes she wonders how much of Islam came to her because of her upbringing, ‘it’s really difficult to know how much of what I believe, I would believe if I hadn’t been brought up with it.’ As an adult, she feels she has developed her own ideas and ways of understanding her faith. It is no easy task, for it is a perpetual battle between the values she grew up with and her own perception and implementation of being Muslim. She recently gave a sermon after the Friday prayer, ‘Even a few years ago I would be like, women leading Jummah? What’s that about? That’s definitely haram!’ However, now she finds herself trying to in-cooperate her faith into her life; how she sees the world and believes it should be like. She’s mindful of the way she dresses and the food she eats. Above all, faith governs the way she acts; encouraging her to dedicate herself to justice and equality.

Being Muslim in London, Wasilat has been able to practise her religion to a certain degree freely. Recently she had felt comfortable enough to pray at a park in Pickenham-Rye, but she recalls feeling very self-conscious and vigilant of her surroundings at the same time. She is not unaware of the genuine fear of Islamophobia and the backlash of being a visible Muslim. On the daily Wasilat feels like she can openly and unapologetically be Muslim; however, the constant government and media propaganda against Islam and terrorism can limit her ability to practice it freely.

But in this same London, Wasilat finds herself belonging to many different communities. To the Muslim communities, the Nigerian community, to the Black community and that of Black women. At times, she feels like she belongs to particular communities she actively participates in, such as activism. She is currently involved in a campaign against borders for children where people from varying backgrounds, beliefs and viewpoints come together to campaign to remove country birth and nationality data in the school census. She organises a lot of picnics and events that bring people together through light-hearted conversations and good food.

Growing up in the heart of a Nigerian community, it had been the only Muslim community she had known of. But it was much later when she became fully aware of the diverse nationalities Muslims could come from. ‘I thought Nigerians were Muslims and so then growing up and realising that actually, all people think all Muslims were Asian.’ She generally feels welcomed into the wider Muslim community.

A feeling of solidarity that comes from belonging to the wider Black community. However, Black itself is an ambiguous category and can mean different things to different people. It is easy to fall victim to oversimplifying being Black, that there is a specific way that spells out to be one. ‘Especially when I was younger, I felt like I wasn’t Black enough. I didn’t listen to the right music. I didn’t have the references.’ Blackness to her now means a much wider and encompassing term.

Wasilat’s name is an Arabic word which refers to the station of an intercessor that Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) will have on the day of Judgement. It can mean a friend or a go-between, and true to the meaning, her name reflects in her personality; her love for people, her proactiveness in helping them and working towards a better community. Wasilat identifies as a Black Muslim woman, a Nigerian, a big sister, the eldest daughter, a Londoner, South Londoner, a photographer, a therapist and a do-er of far too many things. While we have managed to get to know quite a bit about Wasilat, she points out that ‘this is just a snapshot today rather than being something that encompasses all of who I am.’

Based on an oral history interview, written by Navrose Rehman